Apiary News.

March came in like a lamb so maybe we can expect lion-like storms at the end of the month. The temperature shot up to around 13 degrees Celsius on the 1st, and the bees were swirling round searching for scarce pollen sources. I spent several hours pulling out ground elder roots in the apiary listening to the familiar and reassuring sound of bees flying near me. Several newly opened butterbur flowers near when I kneel are visited by a stream of eager bees. Some of them land on me and explore my hands. One investigates a hair on my wrist and tweaks with its mandibles which is a strange sensation but brings a close connection.

Inspections.

I’ll not be opening the hives and disturbing the colonies for several weeks yet. I know what is going on from closely watching the hive entrances and checking on stores. There is no point disturbing them till I see drones and the season has started. Every disturbance increases the colony metabolic rate and stresses the bees to a certain degree. I break the propolis seal when I open up and compromise temperature regulation. In this part of the world we may get very warm days but we often have snow in March and April.

If a colony is without a queen now there is nothing I can do about it. If they have overwintered without a queen there will be other problems to deal with and I would not jeopardise another colony by uniting them. There are no local queens to buy at this time of year and I don’t buy in queens from abroad, ever.

Jane Geddes captures the crocus scene 500 feet higher up from Piperhill where it must have been warm too despite patches of lingering snow on the nearby moors. The moors are shrouded in blue smoke when we walk there later in the week on a still day of damp mist. The smell of burning heather from miles away is redolent of spring, and grouse fly up all around us uttering their strange guttural cries of “geback geback geback”.

Sheep are feeding from plastic buckets of nutritional supplements which is good in that there is not much feed for them on the heather at this time of year, but often the empty buckets are left lying around the countryside for the rest of the year. The sheep on the moors are here to mop up the ticks that would otherwise feed on grouse chicks and impact negatively on the “sporting ” industry. The moors are burnt in patches every year around here to produce succulent new heather shoots to feed the grouse. It’s called muir burning and you can see the action below in these superb photographs taken by local gamekeeper Peter McKinney.

Wild Bees.

We visit the wild bees on a golden day and rejoice at the activity and abundance of pollen loads going in. This colony has survived another winter and is stronger than it was this time last year. See previous blog describing finding this nest in 2019. I’m ever hopeful of collecting a swarm from these survivors that may be resistant to varroa.

Connie and Evangeline come to see the wild bees but they can’t look into the entrance safely without risking bees tangling in hair, so Linton takes a video at the entrance for them to enjoy. Connie and her family have been monitoring the progress of this colony too over the past year on their regular walks.

Storm-felled Tree.

Last week I reported on the ferocious storm that swept through bringing this sycamore crashing to the ground with such force I heard it land from indoors. It filled the woodshed.

Introduction.

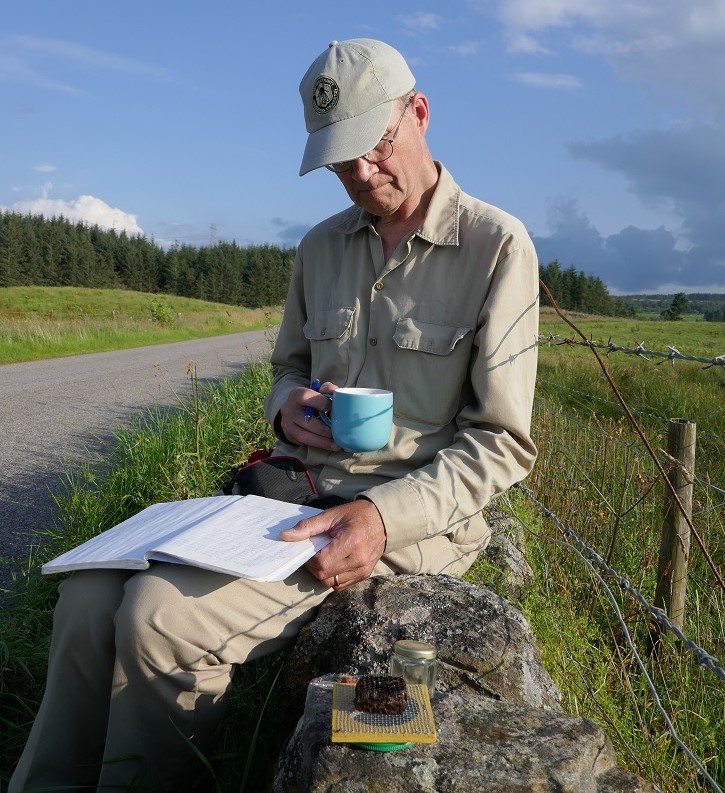

A big warm welcome and thank you to Dr Tom Seeley, Emeritus Professor of Neurobiology and Animal Behaviour at Cornell University, for his excellent contribution on Darwinian beekeeping. Tom’s latest book, “The Lives of Bees” tells us how honey bees live in the wild without human intervention, and his blog will give valuable advice on how we can change some of our management strategies to more closely align with the natural ways of bees. The following photographs have been taken by Tom. By the way, you can buy his book from Northern Bee Books, and also David Heaf’s “The Bee-friendly Beekeeper” and I can highly recommend both books:

Darwinian Beekeeping.

What is Darwinian beekeeping? It is an approach to beekeeping that acknowledges that beekeeping remains, in essence, the exploitation of a wild insect. More specifically, it is set of beekeeping practices whereby humans can exploit their colonies but also disrupt as little as possible their natural way of life. The rationale for this “kinder and gentler” approach to beekeeping is as follows: by keeping colonies in ways that allow them live as they do in the wild, we enable them to experience the living conditions to which they are well adapted, and this makes the lives of our six-legged partners less stressful and more healthful.

What follows is a list of ways in which a Darwinian beekeeper can help his/her managed colonies to live as naturally as possible.

1. Work with bees that are adapted to your location. One way to do this is to rear queens from your hardiest survivor colonies. If you live where wild colonies are common, then another way to get locally adapted stock is to capture swarms with bait hives.

2. Space your hives as widely as possible. This reduces the likelihood of bees drifting among colonies and thus the spreading of disease.

3. House your colonies in small hives. Consider providing just one deep hive body plus a shallow honey super over a queen excluder (to get a modest honey crop). This will encourage your colonies to swarm. Letting your colonies swarm will help them greatly to avoid suffering high levels of the mite Varroa destructor and the Deformed Wing Virus that this mite spreads.

4. Use hives whose walls and lids provide good insulation. For bees, as for us, life is better in a well-insulated home. Conventional wooden-walled hives provide poor insulation.

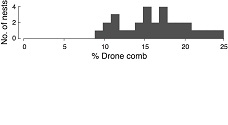

5. Allow colonies to have 10-20 percent of their comb as drone comb. Only healthy colonies produce legions of drones, so having plentiful drone comb in your hives will help improve the genetics in your area. NOTE: this recommendation assumes that you are not treating your colonies with miticides, in which case only your colonies with good mite resistance will be healthy enough to produce plentiful drones.

6. Minimize disruption of nest structure. This will maintain the functional organization of each colony’s nest. In practice, this means replacing each frame of comb in its original position and original orientation after removing it for inspection.

7. Locate your colonies in places that are surrounded as much as possible by natural areas: wetlands, forests, abandoned fields, moorlands, etc. This will help ensure that your colonies have access to diverse sources of pollen and nectar that are not contaminated with pesticides and fungicides, as well as good sources of clean water and propolis.

8. Minimize pollen trapping and honey harvesting from your colonies. Both activities consist in robbing resources that the bees have worked hard to collect for their own needs.

9. Refrain from treating colonies for Varroa. This will help your bees acquire, through natural selection, resistance to Varroa mites. This will eventually happen, probably within five years, if you live where most of the colonies around you are either wild or are being managed by beekeepers who are not treating for Varroa and are not importing queens of mite-susceptible stock. NOTE: you should adopt this suggestion only if you are willing to euthanize colonies that develop high mite counts. By preemptively killing your Varroa-susceptible colonies, you will accomplish two things: 1) elimination of colonies that lack Varroa resistance, and 2) prevention of the “mite bomb” phenomenon whereby mites from a collapsing colony are spread to neighboring colonies when foragers rob out the collapsing colony and bring home its mites.

I hope you have found useful this summary of the logic and the methods of Darwinian beekeeping. The approach is similar to what others have called natural beekeeping, apicentric beekeeping, and bee-friendly beekeeping. Whatever the name, the aim is the same: to put the needs of the bees before those of the beekeeper, so the beekeeper’s manipulations of the bees are done with bee-friendly intentions and in ways that harmonize with the bees’ natural history.

Further reading:

Heaf, D. 2010. The Bee-friendly Beekeeper. Northern Bee Books.

Seeley, T.D. 2019. The Lives of Bees. Princeton University Press.

Making a Start.

Professor Stephen Martin from Salford University in the UK is also trying to help beekeepers find a way to stop treating bees for varroa, and has written a booklet on how this can be achieved gradually over a few years by first reducing the number of treatments. This booklet has been published by the British Beekeepers Association (BBKA) and made available at a very reasonable price. Also coming soon is a guest blog from a beekeeper who is successfully navigating the Darwininan way. You will hear first hand how this is being done on our very crowded little island where there are many more hobbyist beekeepers and colonies close together than you might imagine.https://www.bbka.org.uk/shop/bbka-special-edition-natural-varroa-resistant-honey-bees-new

Thank you for this article is full of wisdom and good advice – the book will be delivered tomorrow 🙂 . I was especially pleased to find number 6 on the list, as so many people said that putting the franes back as you find them it is of no consequence, in a recent arguement on Facebook – fortunately David Charles agreed with me about that point. At the 2019 National Honey Show, I spoke to Ralph Büchler, about a couple of reservations I had about his non-miticide methods for controlling varroa mite populations; firstly the level of experience and expertise needed; secondly what advice should be given to new beekeepers with one or two colonies, given their lack of expertise and huge start-up expenses. Ralph said they should use oxalic acid to deal with varroa mites. I wonder if Tom agrees?

Thank you for commenting, Margaret Anne. You have obviously been thinking a lot about this too. Perhaps Tom will respond himself but my guess is he will do things slightly differently because there are so few beekeepers around him. I was astounded recently to check on BeeBase and find 87 apiaries within a 10 km radius of me. I am going down the Professor Martin path of reducing treatments over a couple of years. I was aware of the problems of miticides (drone fertlity issues for one) some years ago and, like the Danish, have only used oxalic acid for several years (with the exception of formic acid infrquently) I feel as if I am already on the path. I would never let varroa infested colonies swarm or rob out neighbours which is why I treat at all. I would have no hesitation in euthanizing a sick colony to prevent spread of disease. The key I believe is monitoring frequently throughout the season. We might have very low varroa levels at some point but our infested neighbouring colonies could change those dynamics in the blink of an eye.

Yes you are on the right path, Ann. Ofcourse in the UK the mating of virgin queens is so haphazard compared with that in Denmark, Germany and Slovenia.