Introduction.

It’s still cold, but very soon we will be assessing colony health, size and progress here in the Northern Hemisphere. We will make management decisions based on understanding the significance of colony expansion and nectar flow. This week, our regular contributor Professor Tom Seeley explains how we know what informs a colony of its need to build more comb. We learn what makes the bees build new comb and how the scientists discovered this important piece of the beekeeping puzzle. We hope that this blog will be of interest to everyone but especially new beekeepers and those preparing to sit beekeeping exams.

Thank you, Tom, for covering for me this week and taking the time to write this fascinating account of comb building. It is also provides useful information and tips for colony management. It will help beginners understand some of the conditions that accelerate swarming. I shall be back on Friday 28th March. If anyone would like to contribute a piece for Friday 21st please email me.

Comb Building.

Have you ever put frames with sheets of foundation into a hive housing a strong colony, but then found (a week or so later) that this colony had built little or no comb in these frames? If you were puzzled about your bees’ reluctance to build comb, then you will find this Beelistener piece to be of interest. In it, we will look at how the bees that build a colony’s combs— the middle-age worker bees—know when it is time for them to build more comb.

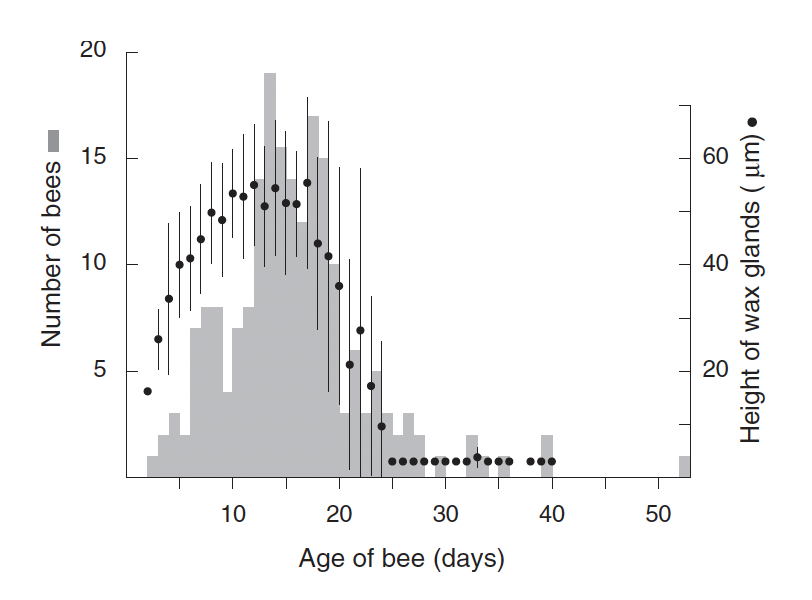

We now know that a colony builds comb only when it really needs to, i.e., when the following two conditions are met: (1) the colony’s foragers are bringing home lots of nectar, and (2) the colony’s combs are nearly filled with brood and food (pollen and honey). Neither condition by itself is a strong stimulus for comb building, but when they occur together then some of a colony’s worker bees are stimulated to build comb. Note: I have written “some of a colony’s worker bees” because the task of building comb is done mostly by a colony’s middle-age workers, i.e., those that are about 10-20 days old. Fig. 1 shows the age distribution of the comb builders in a colony, as reported by Gustav A. Rösch, a student of Karl von Frisch in the 1920s.

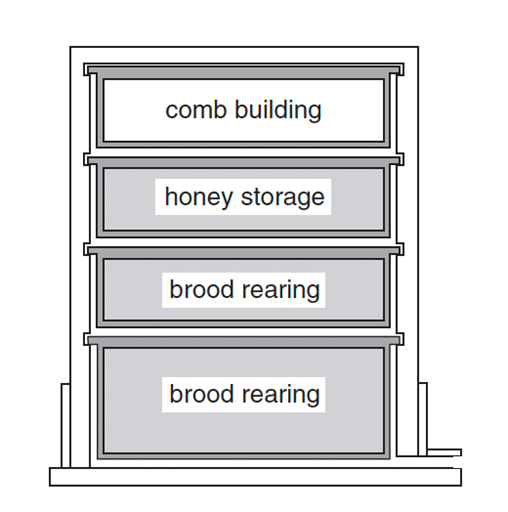

One of my students, Stephen Pratt, investigated the mystery of what triggers a colony’s middle-aged bees to build comb; this was one of the subjects that he studied for his PhD thesis research. Stephen worked with a queenright colony that contained about 5,000 bees and that lived in a four-frame observation hive. Fig. 2 shows this hive. It contained three frames holding fully-built combs; two were used for brood rearing and one was used for honey storage. (A narrow sheet of queen excluder material was laid atop the upper brood-rearing comb, to keep the honey storage comb free of brood.) The fourth frame, on top, started out without comb. It provided a space in which the colony could build additional comb.

Fig. 2. The design of the observation hive used to determine the conditions under which a colony initiates and maintains comb building.

Stephen performed his study in a heavily forested location —the Cranberry Lake Biological Station (CLBS)—in northern New York State. The CLBS is surrounded for nearly 20 km in all directions by pristine forests, bogs, and the open waters of this vast lake, as shown in Fig. 3. The scarcity of natural nectar sources around the CLBS enabled Stephen to have good control of his colony’s rate of nectar intake. He could turn it up or down by adjusting the availability of “nectar” (a sucrose sugar solution) from a feeder that he set up a few hundred meters from his observation hive.

Fig. 3. View of Cranberry Lake from atop Bear Mountain, looking across the lake to the CLBS on the far shore.

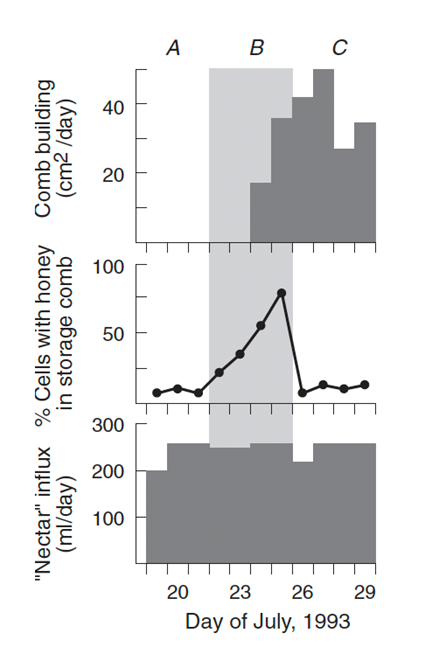

Fig. 4 shows the results of an experiment by that tested whether a colony that is collecting nectar starts to build additional comb only after a high level of comb fullness has been reached. It is important to note that every day, throughout this 11-day experiment, the colony experienced a high rate of “nectar” intake…about 250 mL of the sugar solution that the colony’s foragers collected from the sugar-water feeder that Stephen set up. In other words, the colony experienced a “nectar flow” throughout this experiment.

Fig. 4. Results of an experiment that identified the conditions under which a colony will start, and then continue, to build comb.

During the first 3 days of the experiment (phase A), the colony’s “nectar” (sugar water) intake was high, but its honey-storage comb was kept nearly empty. Stephen achieved this by opening the hive at the end of each day and shaking the honey-storage comb to remove most of the sugar water that the bees had stored in it. We see that the bees built no comb in the top frame during phase A of the experiment.

Then, during the next 4 days of the experiment (phase B), the colony’s “nectar” intake remained high and Stephen allowed the colony to keep the sugar water that its members had stored in the honey-storage comb. So, the percentage of the cells in this comb that contained honey steadily increased. We see that during this second phase of the experiment the colony began to build comb in the top frame. Furthermore, we see that the colony began to build comb when approximately 60% of the cells in the honey-storage comb contained honey.

During the final 4 days of the experiment (phase C), we see that when the colony’s “nectar” intake remained high but the storage comb was rendered nearly empty at the end of each day, the colony continued to build comb.

This experiment shows that a colony will start building comb before it has filled all the existing comb in its hive. I suspect that worker bees follow this strategy to be sure that they have adequate storage space in the event of a strong nectar flow. This experiment also shows us that once a colony has begun building comb, it will continue to do so for as long as it experiences a strong influx of nectar. In other words, it continues building comb so long it has a good supply of energy for wax production and comb building.

Stephen also performed an experiment in which colonies were deprived of a high rate of “nectar” (sugar water) intake, but their storage comb had a high level of fullness (85+ %). He found that these colonies did not build comb. I suspect that the middle-age bees in these colonies did not have full honey stomachs, so they were not stimulated to activate their wax glands.

These experiments show us that a colony starts building comb only when two conditions are met: (1) it has reached a threshold level of comb fullness, and (2) it is experiencing a strong influx of nectar.

Take-home lesson: if you want a colony to produce new combs, then at the start of a honey flow, remove from this colony’s hive any frames with empty drawn comb and replace them with frames with foundation. By removing frames that hold fully drawn but empty combs, one reduces the amount of comb in a hive that is already available for honey storage. This means that the colony in this hive will have to build comb for honey storage, when a nectar flow starts up. Once the bees get close to filling the combs that they already have for honey storage, they will activate their comb building skills and make you beautiful, new combs.

1 thought on “How does a colony know when to build comb? By Professor Tom Seeley.”