David and I recently corresponded about the UK Government’s emergency authorisation for the use of a neonicotinoid to treat sugar beet crops in 2023. It is a controversial issue with two sides to the story and one which David has generously agreed to tackle in this informative and insightful guest blog.

Beekeeping is David’s passion. Like many of us, he greatly enjoys not only learning more about honey bees, but an awareness of the climate and our environment that links to beekeeping. David has kept around 8 colonies of honey bees for almost 10 years near Peebles in Lowland Scotland. He is actively involved with his local beekeeping association which he currently chairs in his role as President. David has a thirst for education and honey bee improvement and has completed all the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association exams.

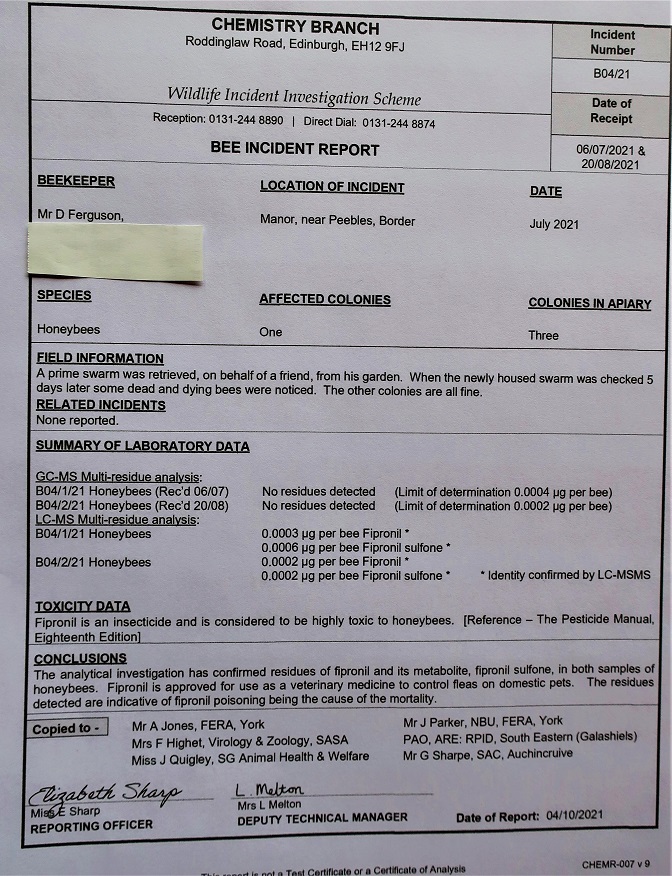

David has personally experienced the shock and heartache of losing a colony of honey bees to Fipronil poisoning in 2021. His apiaries are both sited near farms in the Scottish Borders. Thank you, David for sharing your experience and knowledge with us.

Government Grant Use of EU Banned Neonicotinoids in 2023.

To Treat or Not to Treat; That is the Question?

A Bit of Background.

Sugar beet is an important UK crop, the National Farmers’ Union (NFU), state there are 3,000 farmers who grow sugar beet, and that the wider industry supports around 9,500 jobs in England. Unfortunately, there is a nasty little virus called yellows virus (YV) of which there are 3 types. They are all transmitted by aphids and can cause yield losses of up to 50% if the worst one, Beet yellows virus, (BYV), infects the crop in early June. Infection reduces the photosynthetic area of leaves reducing yield and sugar content. So, in summers where aphids are numerous, which tend to follow mild winters and a warm spring, there is an increased risk of YV damage.

Enter Neonicotinoids.

To reduce the risk of infection from high aphid populations, sugar beet seeds are treated with a neonicotinoid insecticide. This is taken up by the roots and distributed throughout the plant, so insects feeding on it absorb the neonicotinoids.

Neonicotinoids work by targeting the nervous system of insects. They bind to specific receptors in the insect’s nervous system, causing overstimulation and ultimately leading to paralysis and death. They are highly effective against a wide range of pests, including aphids, thrips, and beetles.

One of the benefits of using neonicotinoids to treat sugar beet seeds is that it allows for targeted pest control, without the need for spraying insecticides on the entire crop. This reduces the risk of environmental contamination and exposure to non-target organisms, including beneficial insects such as bees.

However!

There is concern about the impact of neonicotinoids on pollinators, including all bees (honey bees, social and solitary bees) and other insects, as well as potential effects on human health and the environment. In 2013, the European Commission severely restricted the use of neonicotinoid treated seeds to protect honeybees and in May 2018 banned their outdoor use (1), which our UK Government supported. (2)

Since 2018, the NFU and British Sugar (who purchase the entire UK produced sugar beet crop) have applied each year to the Government for emergency authorisation to use neonicotinoid treated seeds, and this has been granted again in 2023. (2)

The derogation refers to the use of Cruiser SB, which is a coating for sugar beet seeds that contains the active substance Thiamethoxam. This chemical, and its breakdown product Clothianidin, are neonicotinoid pesticides. Its use on the 2023 sugar beet crop was only to be allowed if the Rothamsted Virus Yellows forecast at 1st March 2023 exceeded 63% as set out by DEFRA. (3) The forecast on that date has predicted infection of 67.51%.

The Argument for Using Neonicotinoids On Sugar Beet.

The use of neonicotinoid treated seeds is predicated on short term economics – lower yields mean farmers are paid less – plus there are no alternative pesticides available to stop Virus Yellows crop damage.

Of course, our demand for sugar is a significant factor. As NFU President, Minette batters, explained in 2021 “while people continue to enjoy sugar as part of a balanced diet, we should be looking to provide that from our home grown sugar sector. Sugar beet growers in the UK currently produce half of the nation’s consumption of sugar, so many of the cakes and biscuits we all enjoy as a sweet treat are made using British sugar.” (4) It is just a pity we consume as much sugar as we do, which of course is where consumers habits need to change, but that is another topic.

What is happening meantime?

The sugar beet industry is working hard to develop sugar beet varieties that are less susceptible to the virus and to find alternatives to these chemicals.

Prof Mark Stevens, head of science at the Norwich-based British Beet Research Organisation (BBRO), said in March 2021 “there was no reason why developments in seed varieties could not continue the meteoric rise in sugar beet yields, which have grown 25% in the last 10 years”, and he went onto say “We know ladybirds and lacewings have a role to play and there is lots of pressure to harness the natural enemies of pests. We have got some work under way where we are sowing beneficial strips into the crop. We can elevate these beneficial populations and hopefully attract them so they have a greater impact on the aphids. Or, you can pull the aphids into crops which are more attractive to them. We know the aphids prefer brassicas and, in some of our trials, we planted brassicas among them to pull the aphids out of the beet crop and into the brassica, where they cause less damage.” (5)

Argument Against Using Pesticides.

Due to growing pest resistance alternative approaches to neonicotinoids in sugar beet need to be made available to British and other EU sugar beet- farmers.(6)

The risk of environmental contamination and exposure of non-target organisms by neonicotinoids is well documented. (7) The half-lives of neonicotinoids in soils can exceed 1,000 days, so they can accumulate when used repeatedly. Similarly, they can persist in woody plants for periods exceeding 1 year. (8)

Due to the way neonicotinoids persist in the soil, travel through soil and water, and are spread by dust at the time of sowing, the chemicals can end up in wildflowers next to treated crops or flowering crops grown next to or nearby the treated crop. This means they pose a risk even to pollinators that are not visiting directly treated crops.

Neonicotinoids have been found in 75% of 198 honey samples from around the world but fortunately the concentrations detected were below the maximum residue level authorised for human consumption. However, in one-third of the honey the amount of the chemical found was enough to be detrimental to bees. (9)

As Dave Goulson, professor of biology at the University of Sussex, said in a BBC article in 2017, “Entire landscapes all over the world are now permeated with highly potent neurotoxins, undoubtedly contributing to the global collapse of biodiversity. Some of us have been pointing this out for years, but few governments have listened.” (10)

In 2021, Friends of the Earth, via a Freedom of Information request, found that the decision to approve thiamethoxam use in 2020 was made, despite the government’s own advisors recommending against its approval. The RSPB, Friends of the Earth and Buglife, together with around 40 organisations, signed an open letter to the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs in 2021, saying that “allowing farmers to use these harmful pesticides ignored the science and seriously undermined the Westminster Government’s own aims to leave the environment in a better state than it found it.” (11)

The Current Situation.

On 1st March 2023 Dan Green, Agricultural Director of British Sugar announced “Today the independent Rothamsted Virus Yellows model triggered the need to use the neonicotinoid seed coating for this season. This seed treatment is necessary to protect the UK sugar beet crop and farmer livelihoods from the very high Virus Yellows forecast for 2023. The emergency authorisation contains strict controls to protect wildlife, including restrictions on using the treatment near any flowering crops.” (12)

So, neonicotinoid seed coatings may be used for this summer 2023.

What Can We Do?

Gideon Henderson, Defra Chief Scientific Adviser, stated on 13 December 2022 “There is clear and abundant evidence that these neonicotinoids are harmful to species other than those they are intended to control, and particularly to pollinators, including bees. The general ban on use of these chemicals for pest control is well justified scientifically and environmentally.” (13).

In January 2023, The British Beekeepers Association (BBKA) stated that it is “totally opposed to the use of this and similar pesticides due to their effect on honeybees and other pollinators, and the wider environment.” As this matter is urgent, the BBKA would be grateful if you could register your opposition to the use of this type of chemical by writing to your MP.” (14)

Personally, I do not feel that our UK Government gave fully informed consideration from all perspectives, before issuing this year’s emergency authorisation for the use Cruiser SB on sugar beet seeds, particularly with regard to their cumulative and long term effects.

I would like this issue to be debated in Parliament, with the health of our environment put first. To that end, there is a UK Government Petition available at https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/631948 which I have signed and would seek your support to sign it too, if you feel this is justified.

Thank you for your time.

David

References

1 https://tinyurl.com/4vnpcsdt

2 https://tinyurl.com/3pf5zstp

3 https://tinyurl.com/5yurkkb3

4 https://tinyurl.com/2s4297yt

5 https://tinyurl.com/5pm8rcw3

6 https://tinyurl.com/yeythcxn

7 https://tinyurl.com/bdz66rj3

8 https://tinyurl.com/2s3kxv44

9 https://tinyurl.com/3kstrf6s

10 https://tinyurl.com/3dphk4ds

11 https://tinyurl.com/52s3533t

12 https://tinyurl.com/bdtbusz6

13 https://tinyurl.com/4mpc5n82

14 https://tinyurl.com/yckwc85n

If you enjoyed reading this, you can subscribe to receive future posts by email. Also, if this article helped you with your work, please consider making a small donation to keep our site running. You can do this through the “Donate with Paypal” button that appears at the side of the screen if you are using a desktop, or by scrolling towards the bottom of the page if you are using a mobile.

Thank you, Ann 🐝

Surely pesticides also kill invertebrate predators like spiders, wasps, ladybirds which eat aphids. Without giving these populations time to recover farmers are locked into a cycle of permanent pesticide use, particularly if they keep using the same fields for pesticide-laden crops.

Neonics are rather insiduious in killing bees slowly, for example by reducing fertility, and confusing foragers who don’t return to the hive. This allowed manufacturers to claim initially they “weren’t poisoning” bees because there was no obvious heap of dead bees immediately outside hives.

I would be interested in more details of the fipronil poisoning symptoms please? Why did David suspect poisoning rather than, say, paralysis virus?

Hello Paul,

Pesticides are not good for a lot of creatures, included us, depending on dosage and types of chemicals being used.

The instance of fipronil poisoning was in a swarm I collected about 8ft up in a tree, close to a quiet country road. At the time the swarm was fine, I put it in a nuc box and took it to my most remote apiary.

Five days later I noticed some dead and dying bees, crawling, vibrating and unable to fly in front of the hive. Inside there were more behaving like this and a number of dead bees on the floor. I wondered if it was Type 1 CBPV although I didn’t see any greasy looking hairless black bees.

Oops, sent before I finished.

I sent a sample in for analysis and the team at SASA thought it was more likely to be poisoning and their tests showed it to be fipronil.

None of the other colonies in my apiary were affected, so we think that the swarm may have been “treated” by somebody before I collected them.

The lesson I learnt here is to have an isolation apiary, if possible for swarms.

I hope this helps.

David

Is there any evidence that the sugar obtained from sugar beets treated with Neonics contains residues of the pesticide? If there is, could this have implications for those beekeepers who feed sugar syrup to their bees ?

Hello Margaret,

I believe there have been studies that showed there were neonicotinoid residues in sugar, but that the amounts were well below the safety levels set for our consumption. Provided the use of neonicotinoid is not allowed, then presumably our sugar will, over time, contain less neonicotinoid contamination.

After a quick search, I have not come across any articles or studies looking into the question of the effects on our bees by beekeepers using sugar containing residual neonicotinoid contamination. Most studies consider the levels found in nectar, but I would assume even at very low levels they can only be causing some harm.

Hopefully, if we can encourage Nature Friendly Farming (see https://www.nffn.org.uk/ ) and if Governments Globally can reduce our reliance on harmful pesticides , like neonicotinoids, all biodiversity can be maintained and recover.

Regards,

David

Thanks David. One can but hope that pesticide use will reduce. There is so little known about the long term effects on us and our environment…