Last weekend saw some semblance of normality with a trip south to teach practical beekeeping at Newbattle Abbey south of Edinburgh. The challenges of social distancing were mitigated by rigorous risk assessment, and meticulous planning by our hosts. However, nothing could be done about the dodgy weather. Luckily the rain stopped as if on cue during our sessions in the apiary.

I was delighted to explore this field of barley peppered with poppies outside the hotel at the end of the day. It took me back to the 1950’s when summer fields looked just like this.

What do honey bees see?

This evocative scene, redolent of WW1, also got me thinking about how our honey bees view red poppies. Until fairly recently, we’ve been told that bees see red as black and that receptors in the ommatidia of their 2 compound eyes detect blue, green and yellow colours. This is because previous research was based on the assumption that honey bee colour vision would be like ours.

Adrian Horridge, Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University in Canberra has spent most of his career studying vision in insects and has turned our previous understanding on its head. We now know that bees detect only blue as a colour and that they only need this and a few other cues to help them find a flower patch. They don’t have receptors for red or black so these colours are detected as an absence of blue.

I learned recently the concept of phototacticity which has helped me understand the responses of bees to light. If an animal or plant is negatively phototactic it moves away from the light or towards it in a positive response. This happens with house bees and queens who work away in complete darkness in the hive and are negatively phototactic then. It explains why the queen runs away to hide when we open up the hive and expose her. House bees have no sense of circadian rhythm and work round the clock till around 3 weeks when they become positively phototactic in preparation for foraging. This reverse in the reaction to light means they becomes attracted to it and go outside the hive. They no longer work round the clock and sleep at night as foragers. The virgin queen becomes positively phototactic just before her mating flight, and then once laying is negatively phototactic until the colony swarms and she must fly in light again. It demonstrates just how adaptable bees are.

Horridge emphasises that bee vision is about attraction to light and that they don’t have true colour vision. Also, they are not interested in shapes or colours of flowers and need only blue to identify a flower patch. They can distinguish an array of colours as more, or less, blue than the background, vegetation or ground. They do have small green modulation detectors that see contrast at the edges as they scan. The most important feature of honey bee vision is the remarkably rapid rate of adaption to light or dark. It can change tenfold either way in less than a second. You can listen to a short radio interview with Professor Horridge here.

https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/scienceshow/new-ideas-on-how-bees-see/11878004

Implications for beekeepers.

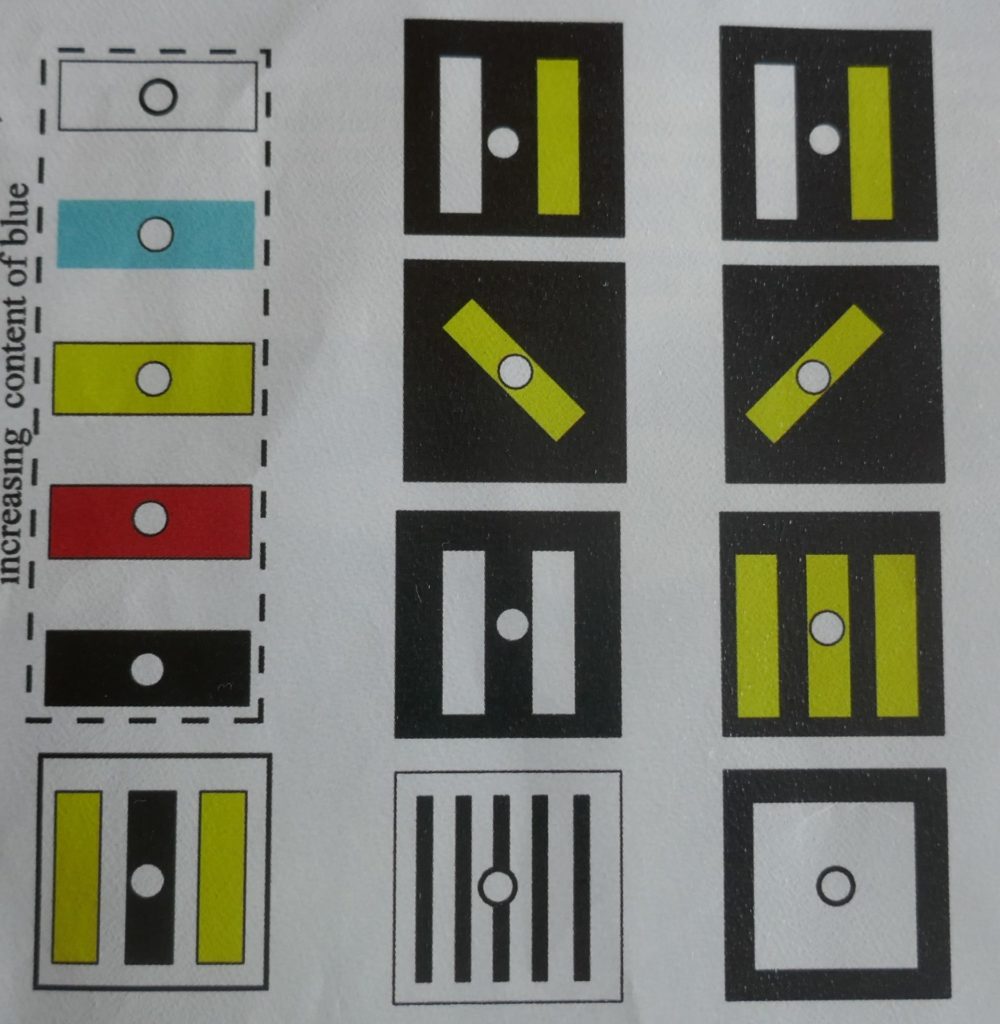

Using traditional hive markings based on previous work (see bottom left) Ukrainian beekeeper Alexander Kommisar found that 50% of his newly mated queens failed to return because they entered the wrong hive and were killed at once. So, he experimented and came up with a new system of hive markings that reduced queen losses and worker drifting between hives.

Kommisar’s patterns are based on the knowledge that honey bees detect, measure and rapidly learn edges with the green receptors of their eyes. With their blue receptors they they detect and measure shades of blue and the relative position of blue to the edges. White is seen as the most intense blue. The yellow bars on black and their position are optimum for detection by the green receptors.

Reference.

Horridge, A. “Why Newly Mated Queens Get Lost”. American Bee Journal, September 2017.

Blaming Swallows.

Maybe our queens are not being gobbled up by swallows, rather they are flying back to the wrong hive and perhaps we could change our apiaries to improve their chances of returning.

Yesterday was fun watching the first 5 of 10 peacock butterflies emerge from their chrysalises. They looked quite crumpled until their wings inflated and dried off. It was exciting watching them fly off out of the open patio door on a warm still afternoon.

I’m waiting for the last 3 to emerge and they are clinging to a nettle stem in a vase so that they can fly freely when I leave the house shortly to help someone find a queen.

Fascinating about the colour vision. I knew that bees had receptors for blue (and E has been planting blue flowers for them) but I didn’t realise the full extent of that. Having been losing queens this year, I’m wondering if my current hive markings might be handled better. Thank you.

This also explains the more than 3 miles and less than 3 feet rule re moving hives.

Really interesting such a straightforward way to avert disaster and it didn’t occur to me. Thanks

Glad you found this useful Tristan.