Visit to Colonsay.

One of the highlights of last summer was a visit in July to Andrew Abrahams’ apiaries on the Inner Hebridean island of Colonsay off the west coast of Scotland. I might have traveled from West Loch Tarbert in Kintyre, but I chose the ferry from Oban because of the more convenient timetable.

Colonsay is a 2 hour and 15 minute ferry journey from Oban with some breath taking scenery to enjoy en route. With nothing but 3,000 miles of wild Atlantic Ocean between the west of the island and the nearest coastline of North America, strong winds and waves buffet the island often. So, it is quite remarkable that honey bees thrive there given the challenges of the cool, windy and often wet environment.

Andrew has been beekeeping on Colonsay for a long time and, during the 1970’s and ’80s he established native honey bee (Apis mellifera mellifera) colonies from isolated stocks acquired from around Scotland. For 10 years he lobbied Scottish Government to establish a native honey bee reserve for these dark bees. In 2013 he was successful and the Scottish Beekeeping (Colonsay and Oronsay) Order 2013 was established. This means that it is illegal to bring any other sub-species of honey bee onto the island.

Scottish Native Honey Bee Society.

Andrew is one of the founding members of the Scottish Native Honey Bee Society and is well placed to advise anyone who is keen to establish colonies of these bees: http://www.snhbs.scot/

Varroa Free.

Colonsay is varroa-free and, because varroacides have never been used, Braula coeca survive here and can be seen on some of the bees. They are harmless creatures, from the Diptera order, and are only intent on stealing food. They often hang out on queens to enjoy a feed of royal jelly as it is transferred from worker mouths to queens by trophallaxis. Apart from some chalkbrood (Acosphaera apis), there is little disease here among the colonies and Andrew likes to keep it that way, so any visiting beekeepers wear clothing provided by him, and they don’t bring anything from their own apiaries over here.

Pollinator’s Paradise.

Colonsay has a resident population of 150 during the winter, but can be busy during the summer with lots of tourists coming to enjoy the beautiful beaches and wildflowers. The island is owned by Lord Strathcona and the farm land was once managed by many more tenant farmers than there are now. They used to occupy the farmhouses dotted round the island but now many of these are rented out to tourists. The extensive wild flower meadowlands provide wonderful forage for pollinators.

Andrew was managing 64 colonies during my visit and they were spread over several apiaries with different attributes. One was in sheltered woodland and another on exposed heather moorland. Normally Andrew divides the colonies among 8-10 apiaries. He breeds from stock exhibiting his preferred honey bee traits and supercedure is high on his list. With mating problems due to cool, damp and windy weather, Andrew believes that supercedure can be a backup against mating failure. With the black bee there is a propensity for perfect supercedure by which the old queen is not killed off by her workers until the new queen is mated and laying. So, mother and daughter queens lay eggs side by side amicably in the colony, perhaps for a few weeks or months. Every year, Andrew sells around 100 free-mated queens and around 20 nuclei. He also runs classes and sells honey: https://colonsay.org.uk/things-do/beekeeping-courses

Gentle Bees.

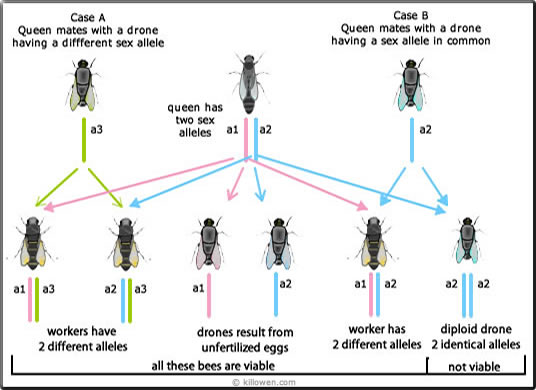

During my visit we inspected quite a few colonies and they were easy to handle. They moved slowly on the frames and were not defensive. Only one colony showed any signs of abnormal brood with some spotty patches of brood, where larva had been removed, indicating that the queen and one of the several drones with which she had mated were closely related. This would happen in times of poor weather when matings take place close to the apiary rather than at a distant drone congregation area. This increaseses the risk of brother/sister matings. By the way, the queen can mate with many drones and 12-17 is about average. They both contributed a copy of the same sex allele to the egg which produced a diploid drone that the workers identified and destroyed just after the egg hatched into a larva. It is a fact that in any population of honey bees there will always be some diploid drones produced and it is not a problem unless a lot more than the average 10% brood are lost from doomed fertilised drones. A colony would dwindle and die off if too many potential bees perished. I will explain the genetics soon. One of my questions to Andrew was about the possible lack of genetic diversity on an island like Colonsay. He reassured me that it was not a problem. Every few years, Andrew sends off bee samples to a laboratory for analysis of sex alleles in the population and the results so far are good. This means that he has never had to bring in new stock of Apis mellifera mellifera queens from elsewhere. However, he has this option, should inbreeding become a problem, of bringing in pure bred queens from Scotland, Ireland or elsewhere.

Diploid Drones.

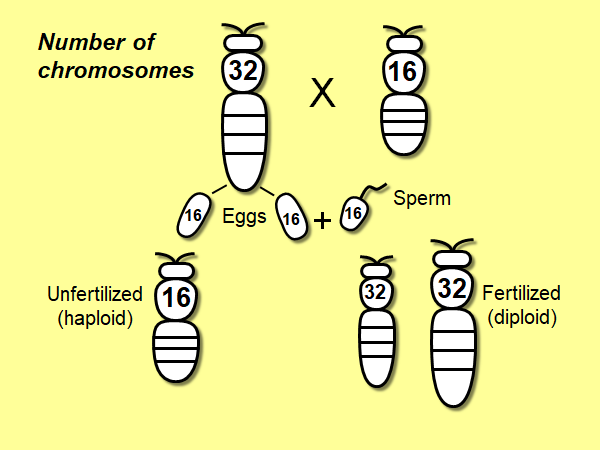

Genetics can seem a bit daunting to some people but a basic understanding is essential in beekeeping when considering queen rearing and queen breeding. Ploidy refers to sets/pairs of chromosomes. Queen and worker bees are female and have 16 pairs of each chromosome in every body cell giving a total of 32 chromosomes. So, they are called diploid. Drones do not have pairs of chromosomes. Intead, drones have 16 single chromosomes and are regarded as being haploid. Haploid drones come from unfertilised eggs bearing 16 chromosome and they are derived directly from the sex cells/gametes of the queen. So, the drone does not have a father but he does have a grandfather from whom the queen inherited some of her genes. Diploid drones come from fertilised eggs and have 2 sets/pairs of chromosomes. Yikes! how can this happen?

Some Terminology.

Genes are units of inheritance formed from deoxyriboneucleic acid (DNA). Tightly packed strands of DNA, and a protein called histone, are inserted into structures called chromosomes which are carried in the nucleus of every cell. For any trait a human has a pair of genes. One gene is inherited from the mother and the other from the father of the individual. Alleles are a form of the same gene but with a slight variation which contributes to the individual’s uniqueness. An example in humans is eye colour variation. Humans have 2 sex chromosomes which determine the sex of the offspring. Female humans have 2 X chromosomes (XX) while males have one X and one Y chromosome (XY), but honey bees do not have sex chromosomes. Instead, they have a set of sex alleles which are called complimentary sex determiner alleles.

The total number of honey bee complimentary sex determiner alleles (csd) is not definitely known, but research indicates that there around 50-80 sex alleles in any geographical region, and potentially up to 145 globally. The paper from a Polish research group found 85 alleles in a group of 6 apiaries within a 3.5 km radius, and 74 alleles in a group of 12 apiaries within a 20km radius. Lechner et al report that alleles range from 53-87 worldwide, but then model that it could be up to 145 globally.

The queen and drone each contribute a sex allele to a fertilised egg destined to become a female (worker or queen bee). However, if these alleles are identical then the egg will develop into a diploid drone which will be destroyed by a worker bees after the egg hatches. The queen has any 2 of these sex alleles and they must be different. Each egg will inherit one of the two alleles. The drone has only one sex allele. If 2 different sex alleles are present in the queen’s offspring it will be female, and if only one sex allele is present it will be an unfertilised male (drone). Sometimes, an abnormal situation arises where the queen and drone contribute the same sex allele. When this happens, usually due to the queen mating with her siblings, the egg is fertilised but develops into an abnormal drone with 2 sets of chromosomes (diploid). You might notice a spotted brood pattern (not caused by foul brood diseases) on a frame and consider the possibility of inbreeding.

Resources.

For more information on genetics in relation to honey bees, I recommend these websites.

http://www.glenn-apiaries.com/principles.html http://www.scientificbeekeeping.co.uk/

Hi Anne,

That is most interesting and really helpful, I have been trying to understand honeybee bee genetics for a long while.

Happy New Year to you and your bees!

Liz

Hello, Liz. I’m really glad that this has been of some help to you. Genetics can be made to sound so complicated in many of the beekeeping books. If you try to get a grasp of cell division by mitosis and meiosis that will help too. I have found some children’s biology lessons very useful in getting a handle on the basics. If you Google the Amoeba Sisters and watch their videos I think that some of the difficult “pennies” will drop.All the best for a great new year to you too, and maybe see you at another Healthy BEES course.

Hi Anne

Stumbled on your blog by accident. Closed colony survival was the subject of a quite heated discussion which took place on the SBAi forum some years ago. Are you aware of this exchange?

Regards

Eric

Hello, Eric. No, I wasn’t aware of this exchange.

Best wishes

Ann.

Hi Anne

Liked your piece on Colonsay – actually spoke to Andrew last night to order my new A.m.m queen for 2021!

Re., the SBAi forum exchange’; it resulted from an article I wrote in the September, 2008, issue of the Beekeepers Quarterly, pp 31-32.

As an aside; have you completed the NDB exam yet?

Best regards

Eric

Hello again, Eric. Glad you liked the Colonsay piece. I learned so much over there. Funny you should mention the NDB, I’m currently head down revising for exams in March and July, with 5,000 word dissertation in between. Botany and entomology portfolios and collections completed, likewise cv/experience portfolio.

Best wishes

Ann

Hi Ann

I commented on the oxalic acid piece. Did it reach you? Are you aware that the VMD have not authorised oxalic acid dihydrate for treating against Varroa.