Introduction to Solitary & Social Bees.

Before we review Laurence Packer’s latest book , I want explain what sociality in bees means. This also paves the way for his amazing account.

Last week, we explored the evolutionary journey millions of years ago of primitive solitary wasp to honey bee. As the name “solitary” implies, this wasp lived alone in a nest doing all the work by herself; making the nest, provisioning it, and egg laying. When the young emerged, they left home as a rule, but over time some genetic mutation caused a daughter to stay at home with mother which was beneficial to the mother to help her produce more offspring. This set the process of the evolution of sociality in motion. Delaplane1 explains that the evolution of sociality was closely linked to nest defence. This makes good sense when you think about how much more efficient a colony of insects is at defending a nest than a single insect.

However, some solitary bees such as miner bees build tunnels to single nests but share entrances, or have entrances close together to increase defences. Solitary bees do not share tasks with family members and they live alone apart from when hooking up with males for mating.

Social Insects.

We know that individual honey bees cannot function and survive alone for long and that they live in colonies with many thousands of members. We call them social or eusocial insects but what does that mean, and how is this system defined? “Eu” is derived from the Greek and means good or true, so eusocial insects are truly social. The hallmarks of being a social insect follow next and they comprise three rules.

Firstly, social insect individuals cooperate in brood care and rearing young that are not their own offspring. It is unusual among most animals to find such cooperative care, because usually the mother gives birth and raises her own young. However, honey bees are different and the queen lays the eggs but leaves the caring of the eggs, larvae and pupae to their older sisters.

The second defining criterion is an overlapping of generations among social insects. Mostly there are two generations, comprising the mother (queen) and her offspring, the drones and workers, in honey bee colonies. And finally, the third criterion defining sociality is the division and sharing of labour. Under ordinary circumstances, the queen is the only egg layer unless, under certain conditions, some workers lay unfertilised eggs. Temporal polyethism refers to the age-related tasks carried out by the two female honey bee castes in the nest. The queen lays eggs only, but the workers progress to different tasks over the first three weeks of adulthood as their hormones and glands develop. By the way, the drone is not a member of a caste because he exits only to mate and pass on his genes which he does outside the nest. The drone has no indoor tasks though no doubt he snuggles up to his sisters sometimes and shares warmth.

Bumble Bees.

Bumble bees are social insects because during spring and summer the daughters stay on in the nest to raise the brood and forage for supplies. They share the work of maintaining the brood nest and they have overlapping generations for part of the year. Some readers may find this confusing because although bumble bees are social insects they spend winter alone, or at least the queen does. At the end of summer, the new queen mates and find a burrow to move into for a winter, leaving the males and workers to die off naturally as they do every year at the end of summer. Bumble bees are social insects even if only for part of the year.

Reference:

1Delaplane, K. S., 2017, For The Love Of Bees And Beekeeping, American Bee Journal, September 2007, pp 898-991.

Book Review.

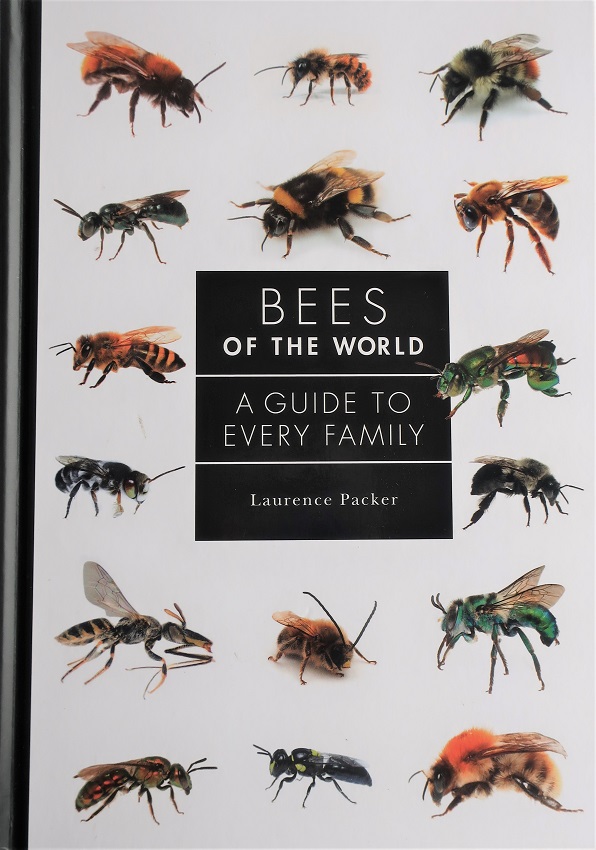

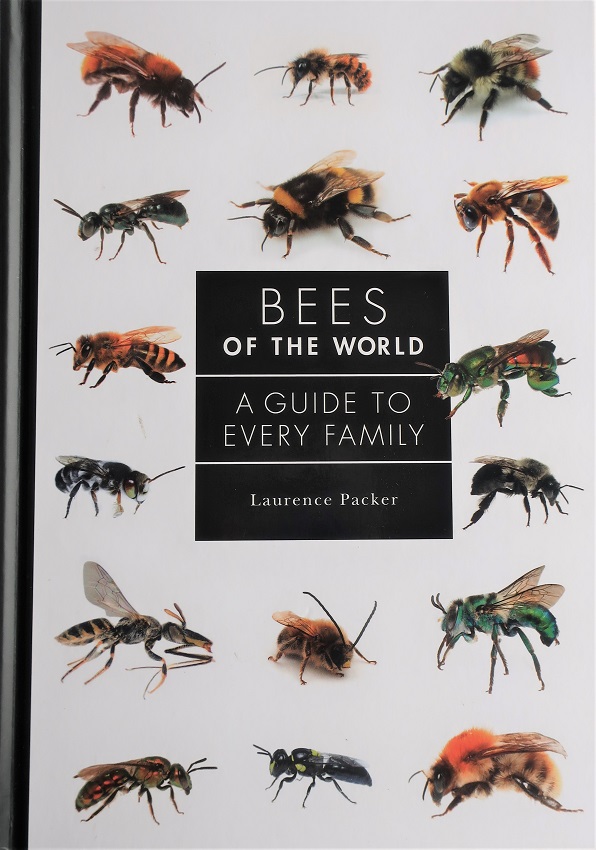

And now we move to our main book review feature this week. Exploring bees though the eyes of melittologist Professor Laurence Packer in Bees of the World is an extravaganza of astounding photography and detailed accounts of the seven living species of bee known today.

Title: Bees of The World: – A guide To Every Family

Author: Laurence Packer

Published 2023 by Princeton University Press, Princeton & Oxford

ISBN: 798-0-691-22662-0

Hardback/cloth cover

Pages: 240

Cost: £25

Available: February 2023 at https://www.northernbeebooks.co.uk/products/bees-of-the-world-packer/.

Bees of The World: A guide To Every Family, by Laurence Packer, contains a lot of valuable information, including how to identify members of the seven bee families living today. The author is a distinguished research professor in melittology (the study of bees) at York University, Toronto, Canada, and is a leading authority on this subject. He shares new information and revises some previous knowledge as science advances. Packer is a prolific and talented writer who delights the reader with his friendly and inviting writing style. The reader is drawn into the incredible world of bees, with which the writer is obviously both familiar with, and fond of.

This is a most beautifully and lavishly illustrated hardback book. It contains perfectly reproduced high resolution photographs on mostly every page. Its convenient size, 17.5 cm x 24.5 cm, makes this book easy to handle. The contents page guides the reader to the introduction and seven sections describing the families of Melittidae, Andrenidae, Halictidae, Stenotritidae, Colletidae, Megachilidae, and Apidae. There is also an index, glossary, and further reading and resources references.

The general readers will find fascinating the diversity of bees on Earth, which arose following the proliferation of flowering plants. The introduction will hold their attention with its brief history of the evolution from wasp to bee and how to tell the two apart today. There are detailed anatomical drawings of the bee body, head, and wings and we learn that the differences in mouthpart are important in identifying the different families. Evolving longer tongues was the first feature that led the Apidae and Megachilidae families along a different developmental route from the other families, as plants evolved to attract and reward bees.

Most insects take their eggs to where the food is as we know from finding butterfly eggs on plants, but bees do it differently. They bring food back to the nest for the brood. Nesting biology is discussed in an amusing way and we read that some bees have been known to nest in and plug up stethoscopes in a field hospital. Ground nesting bees generally choose south- facing slopes in the northern hemisphere, whereas in the antipodes it is the opposite and north- facing sites are preferred. There is an interesting photograph showing a bee making a ball of fluff for the nest by shaving hairs off a hairy plant leaf. An even more captivating photograph shows 20 tiny stingless bees positioned aound a human eye feeding on tears in an extraordinary scientist’s selfie.

Bee food and pollination are also discussed in the introduction. Packer describes solitary bees provisioning the larder before the egg is laid and leaving the offspring to develop to adulthood alone, and he likens it to humans collecting and piling 18 years-worth of food and clothing in a room, then giving birth, and leaving the child to develop alone. Interestingly, bee larvae get most of their nutrition in probiotic form from the microbes that grow on the stored pollen and nectar mixture.

There is a section describing the enemies of social bees such as cuckoo bees and certain wasps that paralyse bees and lay eggs in them so that when they hatch the larvae feed on the immobile bee.

The introduction ends with a useful section describing how the public can help bees and become citizen scientists.

Each of the seven families and their subfamilies are described in detail with photographs of live insects mostly. However, in some cases only pinned collection specimens were available. A world map shows the general location of each genus, and the habitat and characteristics are described in great detail for the scientific researcher or bee enthusiast who needs to identify bees.

Molecular methods for elucidating the phylogenetic relationships among the various sorts of bees have caused scientists like Professor Packer to make revisions, and he explains that classification has undergone changes in recent years, with more subfamilies now recognised than previously. These advances, along with lots of work by a growing number of biologists, driven by the growing concern for pollinators in general, make this a timely publication.

Thank You.

We reached the end of January at last and slid into February with sighs of relief as early flowers like snowdrops, aconite, sweet box, and witch hazels appeared in some parts of Northern Hemisphere. Welcome to all the new beelistener subscribers who joined this month to read the weekly blogs Thank you to everyone who engaged and made comments. I also thank those of you who generously donated to the upkeep, maintentance, and safety of this site. I really appreciate this because it means that you can enjoy reading without having annoying advertisements popping up. Finally, welcome to all the new readers including those from Jordan and North Macedonia the two new countries to join the 139 countries of the world who read this blog.

A late congratulation for having one of your photos chosen to be included in the Vita beehealth calendar of 2023

Aw, thank you Paul. That was kind to mention it. I love having the calendar on my desk as it fits perfectly on the edge of a bookshelf.