Colony Death.

When does a colony die? Is it with the loss of the old queen and the end of her line of offspring, or when the whole colony succumbs? Scientists might use the first definition, but when it all boils down to us losing bees we are usually devastated and what went wrong is all that matters in order for us to learn from the experience.

Poisoning?

On seeing the photographs of hives at a field bean crop, I thought that the bees above had died of poisoning.What happened was, the beekeeper had arranged with a farmer to bring a few colonies of bees to field beans. He was given notice of crop spraying by the farmer and so he shut up his bees for 24 hours. However, not having previous experience of taking bees to crops, he hadn’t provided extra ventilation or access to water required to cool the hive during the period of confinement, What would have saved the bees was for the front entrance to have been covered in mesh, and an extra shallow or deep box placed on top of the supers with a water feeder for the bees cool the hive. A mesh travelling screen could have replaced the crown/cover board. The open mesh floor was in place but there was still not enough ventilation in the poly hives for the bees to survive suffocation.

Suspected Poisoning.

A couple of summers ago in August I noticed wave after wave of worker bees tumbling out of one hive and spinning on their backs with proboscises extended. This went on for a few weeks with hundreds of bees dying over that time. There was no crop spraying that I knew of in my area, but someone suggested that potatoes might have been sprayed within flying distance.

So, I contacted SASA (Scientific Advice for Agriculture in Scotland) in Edinburgh, and sent off 2 samples of 200 bees to Elizabeth Sharpe in the Chemistry Branch. I kept a third sample of bees in my freezer should they be needed for evidence in a possible future court case over poisoning. However, the samples came back negative to pesticides. Had facilities been available to check for virus loads, using polymer chain reaction (PCR) tests on bee DNA, tests might have shown that the bees had Chronic Bee Paralysis Virus Type 2 (CBPV) as the cause of death. If you look closely at the bees above you will notice that some are black, hairless and shiny. This is typical of the “black robber bee” appearance of bees with this disease. Mostly the bees were dying where they landed on the concrete slab outside the hive, and they didn’t crawl far.

We are all painfully aware today that viruses spread easily and quickly when animals are crowded together. This colony had been large and strong but confined for long periods over a harsh spring. CBPV is not associated with varroa but this colony did have a high burden at the end of that summer. When they survived winter, I put them onto fresh combs and foundation and burned the old ones last year. Now they are busy bringing in lots of pollen on good days. However, this spring is slow to start and today is very cold on the 2nd April. It is snowing as I write. So, it remains to be seen how this colony fares in 2020.

Friend shares hive history.

Imagine the beekeeper’s disappointment, having prepared a colony well for winter, on opening up and finding this in spring. The sparse number of dead bees have been shaken off this frame, but you can see evidence to suggest that there were not enough bees to ventilate the hive and recycle some of the moisture, so the frames became moldy. Without sufficient bees to keep brood warm, chalkbrood has flourished. There were plenty stores left. The queen was over a year old and may have been the cause of the colony demise. Sometimes the queens don’t get well mated and so fail earlier than we expect. For whatever reason this colony dwindled and died but it reminds us that large numbers of bees are required to generate heat in the winter cluster and keep the colony alive over this long period.

Dwindling Colony.

This colony never did very well. I bought the queen from a friend on the west coast of Scotland because I was keen to introduce native dark bees (Apis mellifera mellifera, Amm) to my apiary. At the time, I was using the large 12×14″ brood frames but, with hindsight, the colony would likely have done better in a single standard brood box. It was interesting to notice that these bees didn’t build up in spring early enough to take advantage of the oil seed rape crops nearby. Nor did they get ready to swarm as early as my home bees. They did collect enough stores to get through the first winter without my harvesting any honey though. They continually behaved as they would have done on the west coast, building up and swarming much later in the season despite good early forage on the other side of the country near the east coast.

At the end of their third winter, I found lots of frames spattered with faeces. We call this dysentery in beekeeping though that is not totally accurate given that dysentery is an infection and this faecal spattering is caused by too much water in the bee gut. It is not a disease. It may arise from ingesting fermented stores, or having been fed dilute sugar syrup at the end of summer when it is too cold to evaporate off excess water. When bees are confined to the hive for too long and cannot take cleansing flights, to evacuate their rectums, there may be spattering of faeces around the hives. It is not specifically caused by nosema but it can be associated with this microsporidian fungal infection of the bee gut (ventriculus).

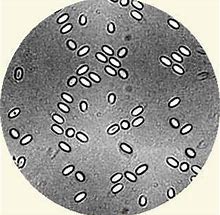

In this situation, I collected a sample of 30 bees and crushed the abdomens to examine the contents under my microscope. I found some Nosema apis spores resembling pudding-rice grains. The colony died and I destroyed the frames because spores can linger for several years in comb. Some people may have chosen to fumigate the frames and comb with acetic acid 80% as it is effective in killing spores but I take a belt and braces approach to disease control and destroy equipment when in doubt.

Testing for Nosema.

Recently I was teaching on an adult bee diseases course when one of the students had a eureka moment on testing his sample of bees for nosema. He had taken the sample from a colony that had never done very well. We’ve all had one or two those sort of colonies during our beekeeping careers: they just get by and no more, but you don’t get much of a honey harvest and the traffic in and out of the hive is never heavy. Anyway, the sample was full of Nosema apis spores and Kelvin was able to plan management based on his diagnosis and knowledge of the colony. If a colony seems strong enough to save, performing a Bailey Comb Change is the usual management strategy here. You can find out how to do this on Bee Base.

http://www.nationalbeeunit.com/index.cfm?pageid=173

Dealing with Dead Colonies.

If possible, carry out a postmortem and find out the cause of death. This season it will be difficult to do this in detail if you need a mentor to look over the colony with you. However, you can take photographs and check back on records to provide a good history and then seek help over the phone or by email.

Sometimes you can be fairly certain that the colony didn’t have enough bees to keep warm and move to the winter stores, so have died of isolation starvation. But what if there is some disease lurking in there? It is always good practice to seal up a hive when you are unsure about the cause of death to prevent robbing out by healthy colonies from your own or another apiaries. This will reduce the risk of disease spreading between colonies. My friend and colleague Tony Harris has written an excellent article about carrying out hive autopsies and he kindly shares his experience with us:

What To Do With Old Comb and Equipment?

Old comb can contain fungal and bacterial disease pathogens as well as residual pesticides from varroa treatments and agricultural chemicals picked up in the field by foragers. Recent research also shows that varroa mites prefer breeding in old comb. Pathogens causing American foulbrood and nosema can linger for years in wax, chalkbrood spores also. It is possible for viruses to end up in wax but it is not known for how long they survive there (Milbrath, 2020, American Bee Journal, March). Because of its composition, wax, with its hydrocarbons, can absorb chemicals such as varroacides. This may lead to varroa being exposed to continuous low doses of varroacides which risks possible development of resistance to treatments. Studies carried out in 2012 by Wu et al demonstrated that bees reared on high-pesticide combs had delayed development and died earlier than the control bees in the experiment.

Comb Making Costly for Bees.

Professor Seeley’s 1985 research shows that making new comb is costly to bees and it takes around 7.5kg (16.5lbs) honey to rebuild a brood nest. We also know, from studies by Delaplane and Berry in 2001, that brood nests made on new comb have a larger area and the bees emerging from new cells are of higher weight than those raised on old comb. Old comb contains a build up of larval skins (cocoons) so cell size decreases. So, we have to weigh up the cost to the bees of making new comb over the need to get rid of the old comb and reduce diseases.

Risk Assessment.

Best practice is to change brood combs every three years. This can be done gradually by moving a few old combs to the outside of the brood box and removing them in spring so that at the end of year 3 all the combs are fairly new. It is a continuous cycle of annual comb change. A shook swarm or Bailey Comb Change will achieve a change of combs fairly quickly in one season and these are my preferred methods. See Bee Base for instructions.

Beekeepers have to decide what to do with old frames on the death of a colony based on making their own risk assessments.Wooden hardware and hive bodies can be scorched with a blow torch, while polystyrene can be cleaned with bleach and washing soda.Wooden frames may be boiled in washing soda and reused but wax is tricky and whether to use again or destroy it requires consideration. I hope that this blogs gives some new information to help you make good decisions in your apiary, and that your season goes well.

I enjoyed reading this blog. Most refreshing.

Thank you for commenting, Margaret. I’m glad that you enjoyed reading the blog. There will be a follow-up soon on the subject with a guest blog from Jane Geddes.

Ann, your article on Scottish Heather in the Bee Journal is enthralling. I have sent you a message on Messenger. x

Thank you, Margaret. I wrote that article in an attempt to attract some of our beekeeping colleagues from across the water to our 2016 SBA convention in Elgin. It is too complicated to explain why I cannot use Messenger but sadly I didn’t receive your message. FB or email work well for me. I am always keen to get pieces for guest blogs if you have anything to share and the time to write. It is warming up here and I think that the season will start next week with the bees bursting at the seams judging from the activity and pollen loads going in. I can’t wait to do my first inspections.

Excellent presentation of important information, Ann. Thank you for sharing it. I especially appreciate your description of what you saw with your colony that had a bad infection of Chronic Bee Paralysis Virus, a disease that has not yet appeared (to the best of my knowledge) in my colonies over here in Ithaca, New York.

Thank you, Tom. I’m glad that you liked the blog, and I hope that you don’t find CBPV in your colonies.

Most helpful and informative, thank you Ann

Good to know, Liz, thank you for telling me. I hope that your and your colonies do well this season.

Hi Ann,

Sorry to hear about Jane’s colony which seems to have passed away through isolation starvation. When I first learned about bees, my mentor told me that going into winter, “the best insulation for bees is more bees”.

Thank you for highlighting all these problems and telling people what they can do to help prevent them.

Hello Ruth, thank you for commenting and sharing your knowledge.