I’m writing on the summer Solstice, June 20th. I thought it was always the 21st, but Susan Jardine is a keen celebrator of this seasonal marker and tells me that sometimes it is on the 20th, though the last time this happened was in 1796!

Reducing Brood Space.

Soon I shall be confining the queen and her egg laying to the bottom brood as egg laying reduces. A queen excluder between the brood boxes means that their winter stores will be collected in the top brood box and I shall take any surplus from the supers above that.

I hope that you have had better queen matings than I’ve had here. I’ve had to put 3 test frames with eggs into colonies that have been broodless for several weeks. For one colony it’s nearly past the time for a virgin queen to be able to mate. Fortunately, I’ve kept the old queens from swarm control and can unite them back if need be. They were produced last year so I have no concerns about them going into another winter.

So many cold wet weeks in late May-June this year, but now for the last part of June it is warming up again. The Robinia pseudoacacia trees are in full bloom with creamy white yellow-tinged flowers that attract the bees like a magnet. Clover is blooming and there is enough forage, if the weather holds. None of the colonies, apart from nuclei, needed feeding this month. I gave the nuclei dry sugar sprayed with water to reduce the risk of robbing and they are doing well.

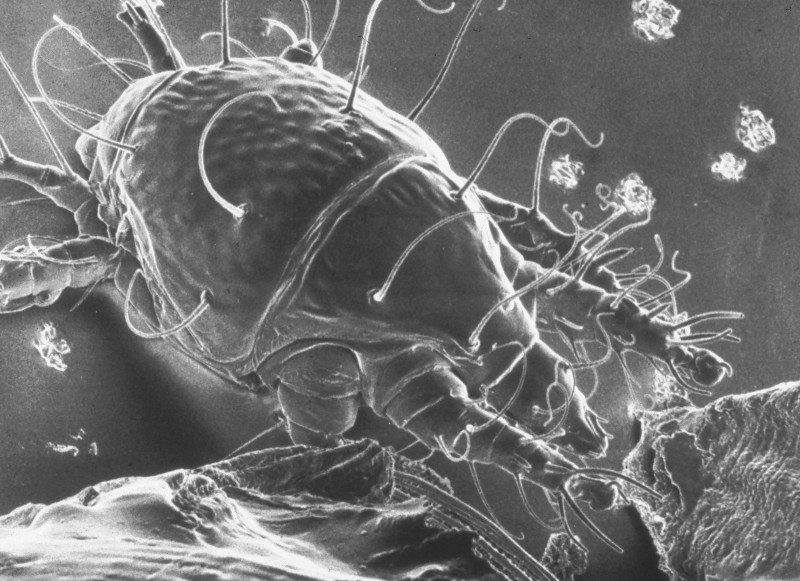

Researching CBPV.

I’m preparing a presentation on chronic bee paralysis virus (CBPV) at the moment and my research leads me side-tracking down other interesting paths in the process. Did you know that the Isle of Wight Disease was almost certainly caused by a virus, probably CBPV? What is really interesting is that the UK media of the early 20th century sensationalised unprecedented bee losses that had reached almost epidemic proportions on at least three occasions over the first twenty years of last century. Sounds familiar doesn’t it, the media talking up fake news with the parallel today being honey bees in massive decline.

The media latched onto the idea that honey bee deaths were caused by tracheal mites (Acarapis woodi) after their discovery in 1919. There was no scientific evidence for this yet beekeepers too promulgated this myth. Indeed, when I started beekeeping twenty years ago our local association was still teaching this, and it would not surprise me if some beekeepers still do today.

UK Scientists.

We are very fortunate in the UK to have some distinguished scientists, and most of them are happy to share knowledge and communicate with curious beekeepers. Dr Norman Carreck sent me all the references and links needed to convince me that tracheal mites had nothing to do with the decimation of honey bee populations back then. I’ve been reading articles by one of beekeeping’s heroes, Dr Leslie Bailey. Dr Bailey worked at what was once known as Rothamsted Experimental Station.

Dr Bailey was recruited by Dr Colin Butler (who identified queen substance) to join the team at Rothamstead Experimental Station in 1951 in the bee pathology department. He arrived at an exciting time when insect pathology was just starting to get attention and he made massive contributions to this much needed area of research.

Bailey was a pioneer in the study of insect virology. He debunked the theory that the Isle of Wight disease was caused by tracheal mites as he isolated viruses including chronic and acute paralytic bee viruses. Another of his most important pieces of work was isolating the cause of nosemosis. Not only did he describe the causative organism, but he devised practical ways of managing colony hygiene, and the Bailey comb change is named after him. He also isolated the cause of European foulbrood bacteria in the new genus Melisssococcus.

Bailey’s most famous book, Honey Bee Pathology, is one of the most comprehensive texts on bee diseases and is of great relevance today. Bailey became leader of the pathology department until 1982 when Brenda Ball took over on his retirement. You can read more about him here: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0005772X.2017.1387429

Isle of Wight Disease.

Bailey’s papers provide an interesting account of the mystery malady1that would be talked about for decades. Beekeepers on the Isle of Wight started losing their bees during 1906 with some losing most of their colonies. They found bees crawling from their hives and dying. Although there was no evidence that this was a new disease, the popular press at the time sensationalised these events. Interestingly, the spring of 1906 was especially harsh. After a spell of warm weather in April, when the colonies collected a lot of nectar, May temperatures dropped in London to -5 degrees Celsius on the 2nd with snow to follow. The bees would have been confined to their hives after collecting nectar, and it sounds like they presented with severe symptoms of dysentery (“diarrhoea” from too much water in their digestive tracts).

One of the first scientist on the scene was Dr Imms who examined infected bees in 1907. He didn’t know much about honey bees it seems, and his drawings showed bees with too much water in their distended guts, most probably from confinement to their hives rather than disease as such.

Colony Deaths Across the World.

Across the world between 1901-1905, beekeepers in Italy, Brazil, Canada, and the US were reporting colony deaths with symptoms of affected bees crawling from their hives in a similar manner to what was now dubbed the Isle of Wight Disease (IOWD). In Utah, 2,000 colonies were lost as bees dropped to the ground, climbed grass stems, and died. Colonies in Australia and South America started dying too after crawling. Since there was no parasite found to have caused this, poisoned forage was suspected though nobody really knew and it could have been a virus.

Beekeepers Unwittingly Kill Colonies.

Back in the UK, there was much speculation but no research evidence to base any treatment on. Many hundreds more colonies were killed by beekeepers fuelled by mistaken fallacious beliefs. One unfounded theory was that the diseased bees were short of nitrogen in their diets because pollen was found in their distended rectums. We know now of course that bee faeces are yellow due to pollen which is perfectly normal. However, the beekeepers took away frames of pollen as the bees got ready for winter and substituted beef extract to restore the nitrogen. We have visions of beekeepers brewing up Bovril for their bees. This went on for several years. Other deleterious doses of phenol, formalin, sour milk, salt, Izal disinfectant, and other lethal remedies were administered to these poor bees and their deaths were attributed to IOWD by their keepers.

Dr Rennie and colleagues first identified tracheal mites in 1919. They were named Acarapis woodi after Mr Wood the financial sponsor for the research project. Although Dr Rennie’s own results did not support tracheal mites causing IOWD, he considered it a possibility. His report was first published in 1921 by the Royal Society of Edinburgh. The press was to have a field day with fake news which no doubt convinced the beekeepers of that time that tracheal mites were to blame. This legend was to last many years.

Tracheal mites could not have caused such widespread colony losses because they appeared in the tracheae of foraging bees in normal healthy colonies as well as in diseased ones. Sometimes foragers had blackening and thickening of their tracheae but it didn’t stop them flying and only slightly shortened their lifespans. Interestingly, tracheal mites increase when the weather is poor, or when there is a poor nectar flow and foragers stay at home and infect nurse bees. Bailey tells us that tracheal mites become almost extinct in countries with continuous nectar flows.

Another really interesting observation of Bailey’s was that A. woodi flourish and multiply in lean times of competition for forage. Back in the 1900’s, there were ten times more colonies in the UK as there were in the 1990’s. Beekeeping had been revolutionised by moveable frames, and bee farming on a large scale was now possible at the beginning of last century. The scene was set for tracheal mites to thrive in overcrowded apiaries with forage competition.

Everyone likes a scapegoat when one’s management might be the cause of a problem. We often hear today that winter losses are caused by isolation starvation despite plenty stores, so the beekeeper is not to blame for not attending to food stores. However, why was the colony so small that it could not reach the precious stores? Might heavy varroa loads not be the root cause? And so, it was the same with IOWD which was assumed to be the cause of problems for which there was no known explanation.

It would be another fifty years before Dr Bailey discovered the virus responsible for the crawling bees, but, when tracheal mites were discovered the press had a field day with fake news telling the country that the bee-killing parasite, A. woodi, swept Britain in 1911 and 1912 and flowers blossomed to an almost bee-less spring. On the contrary, beekeepers all over the country reported bumper honey crops in 1912.

We are only human after all and can be forgiven for our failings, but one thing for sure is that we live in an era when there is so much research-based evidence out there that we cannot claim ignorance when faced with the responsibility for the welfare of livestock.

Reference:

Bailey, L. (1964). The ‘Isle of Wight Disease’: The Origin and Significance of the Myth. Bee World, 45(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/0005772X.1964.11097032

Good clear information thank you Ann.

Thank you, Rick. Glad you found it useful.

Such great information and research Ann. Bees really are at the mercy of beekeepers but as you say beekeepers don’t need to be ignorant of the best info out there and it’s thanks to yourself for bringing issues like this to their attention. Every bee keeper needs to subscribe to your blog!

Thank you, Susan, for being a steadfast supporter of bees, and commenting so positively on many of my blogs as I endeavour to share info and promote honey bee health.

Thank you, Ann, for your review of the history of the misunderstanding (“myth”) of the cause of the Isle of Wight disease. This error did indeed arise because the discovery of tracheal mites occurred around the time of heavy winter losses. This story is a great example of thinking that a correlation shows causation.

I appreciate, too, your giving kudos to Dr. Leslie Bailey, whose 1963 book Infectious Diseases of Honey Bees is first-rate and remains a valuable read. I wish I had been able to meet him when I visited Rothamsted (to talk with James Simpson, about his experiments on what causes swarming) in the summer of 1972.

Thank you for your positive comments, Tom.

A bee virus?

🙂

What if, electrical pollution was the true cause for IOWD?

I highly recommend reading the following book (>100,000 copies sold!)

“The Invisible Rainbow” is the groundbreaking story of electricity as it’s never been told before–exposing its very real impact on the biosphere and human health.

Over the last 220 years, society has evolved a universal belief that electricity is ‘safe’ for humanity and the planet. Scientist and journalist Arthur Firstenberg disrupts this conviction by telling the story of electricity in a way it has never been told before–from an environmental point of view–by detailing the effects that this fundamental societal building block has had on our health and our planet.

In “The Invisible Rainbow”, Firstenberg traces the history of electricity from the early eighteenth century to the present, making a compelling case that many environmental problems, as well as the major diseases of industrialized civilization–heart disease, diabetes, and cancer–are related to electrical pollution.

Sincerely

Well you never know, you could be right. Thank you for contributing, Hurukan.