The season is over for me as I harvest the last 2 honey supers and a box of Ross rounds. After more rain in August, we have warm days with spells of sunshine and the bees continue to collect nectar from the Himalayan balsam at the river. The leatherwood tree (Eucryphia spp.) in the garden is loud with foraging honey bees, and a myriad of other noisy pollinators.

Beekeeping Associations Collaborate.

My local beekeeping association collaborated with a neighbouring one to organise an afternoon of colony inspections on the last Sunday of August looking specifically for brood diseases. We don’t have an association training apiary yet so we were grateful to our hosts for opening their apiary up at the very end of the season when the bees are preparing for winter and prone to defensive behaviour. The weather is unreliable now but we were incredibly lucky because it was dry and the sun shone during part of the afternoon.

Training.

Scotland’s Bee Advisor, Lorraine Johnston, from SRUC (Scotland’s Rural College) came up from Dumfries to lead the afternoon training session. Lorraine was supported by local Bee Inspector, Julie Sievewright, from the Scottish Government Bee Inspectorate. We had a great turnout of enthusiastic beekeepers and 24 was the perfect number to form groups of 6. This meant that Lorraine and Julie gave 2 demonstrations each leaving plenty time for questions over the hives.

Foulbrood Outbreak.

The timing was perfect given the increased outbreaks of foulbrood this season with European Foulbrood (EFB) having been found close to home recently in Nethybridge. Lorraine attributes the increase partly to the poor season weather wise with stressed colonies, and much more swarming than usual. There are implications here for better control of swarming, and monitoring carefully colony food stores in times of poor foraging weather.

Why and How to Inspect.

Why should we inspect our bees specifically for disease and when should we do this? Well, we need to know the health status of all our colonies so that we can deal with any problems promptly to prevent them collapsing, and so that we can reduce the risk of spreading diseases. The ideal times for two dedicated disease inspections are in spring at the start of the season and at the end of summer.

Hygiene.

Lorraine and Julie prepared for the demonstration by making up a bucket of soda crystals with water and a few drops of dish washing detergent to wash hive tools and gloves between inspections. We all disinfected our boots by spraying them (including the soles) with a strong disinfectant called Virkon S which is used widely in laboratories and in farm biosecurity. It kills over 500 strains of viruses, bacteria, and fungi. It was used widely during the foot and mouth outbreak at the start of this century in the UK. It is sprayed onto hard surfaces and kills 99.999% microorganisms in less than 10 minutes. It can be disposed of down sinks and drains but must not be chucked onto the ground or released into unprotected water systems.

We all wore disposable nitrile gloves and a few people wearing leather gloves donned a pair of nitrile ones over the top of them. The inspectors wore two pairs of nitrile gloves to reduce the risk of contamination should they find disease that required changing gloves because hand washing is not so easy in the field without running water, and bare hands are protected by the first pair of gloves.

With well lit smokers, the inspectors approached the first colonies and lightly smoked the entrances. Best practice is to inspect last any colonies reputed to be very defensive, and any colony suspected of having disease which makes good sense and important to remember when inspecting your own apiaries.

The diseases that we are interested in are the notifiable ones which are European foulbrood (EFB) and American foulbrood (AFB). We studied up the signs and symptoms before the training session but a quick reminder; we were looking for greasy sunken cappings with pepper pot appearance on the frame with AFB. The disease is usually contracted within the first 48 hours of larval life but manifests after cell capping. The field test is roping of larval material more than 2.5 cm when poked with a match stick which is disposed of in the smoker. There are lateral flow devices but only bee inspectors are legally allowed to handle AFB in the field in the UK, so we would not carry these test kits ourselves.

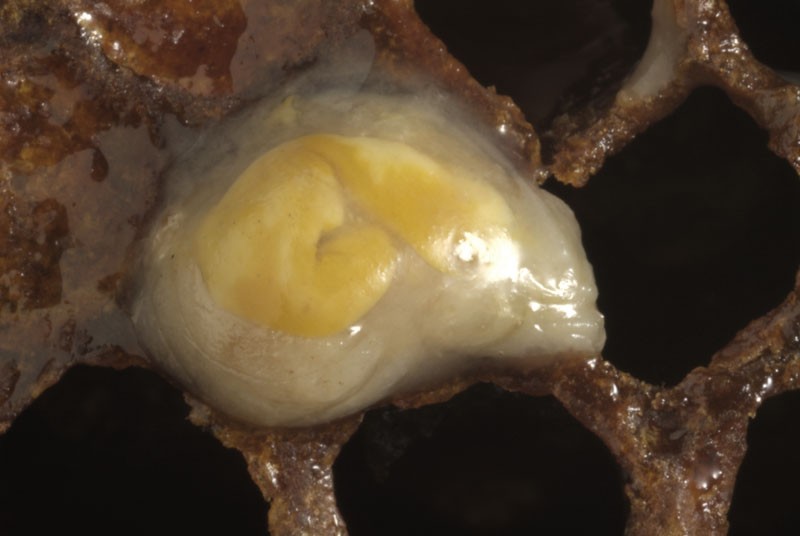

EFB is also contracted early on in larval life and usually kills the infected larvae when they are 4 or 5 days old. They are seen before cell capping as yellow, discoloured, twisted, unsegmented, and melted looking larvae.

We keep a look out for other diseases such as nosema, chalkbrood, sacbrood virus, chronic bee paralysis syndrome and varroosis.

Method.

Lorraine removed the roof and placed it to the side out of her way. She kept the shallow honey super covered by the crown board to reduce the risk of robbing and placed it on the upturned roof. She removed the queen excluder carefully checking that the queen was not on it. She placed that on the covered super. The first frame contained stores only and was placed at the front of the hive in case the queen had been missed and she could return in the front entrance. Bee inspectors like dummy boards as these make hive inspections easier on the bees and frames don’t have to be placed on the ground.

Lorraine’s plan was to check every frame for the queen before shaking it. If she found the queen, she would place the frame back and continue shaking bees off the other frames and inspecting them. Her strategy was to allow the queen to move quietly to another frame so she could inspect the missed frame safely. This is a good strategy and means that inspectors are not responsible for handling other people’s precious queens. Removing bees from the frames is essential and key to inspecting each brood cell. Shaking the frame with a sudden stop removes the bees efficiently in most cases.

It is important to open any cells that are perforated or look suspicious. Sometimes cells are perforated because the bees have not quite finished capping them, or they have deliberately uncapped them as part of varroa sensitive hygienic behaviour.

Lorraine used her hive tool to open a perforated cell but fortunately only found chalkbrood. She pointed out sac brood and a few bees with deformed wing virus, both of which are vectored by varroa. The demonstration was excellent because it was carried out efficiently though slowly enough for onlookers to see everything and ask questions. Frames of interest were passed round the group. The bees were feisty and clearly not happy about being inspected at the end of the season when they are frantically collecting and defending winter stores but they were handled carefully and were well behaved bees and nobody in our group was stung.

Advice.

Lorraine’s advice is to notify the Bees_mailbox@gov.scot if you live in Scotland and find any suspicious brood cells during an inspection. Most importantly, learn how to identify brood diseases and how to inspect a colony for disease. Know how to tell the difference between notifiable and common diseases and report any suspicious disease. For further information: https://www.gov.scot/publications/honey-bee-health-guidance/pages/inspections/

Valuable Recourses.

One of the key things about a training day like this is that beekeepers who have had no previous contact or experience with bee inspectors can learn that they are a valuable resource and a great support to beekeepers. They are on our side! We all have the same goal of improving bee health and it is easier to do this in collaboration with others.

Just read a really interesting article in the New Yorker by Sam Knight called Is Beekeeping Wrong? Tom Seeley talks about a lot of the work he has done and John who is a natural beekeeper. I didn’t realise that there is a lot of worry over the possibility of displacement by honey bees on other pollinators as there are now so many bee keepers around the world. Interesting reading.

Interesting comments, Susan. Yes there is no global shortage of honey bees though they are at risk from many factors. At last the message is getting through that we don’t need people to keep bees to save them. Rather we need everyone doing something for all pollinators. Just as you do with your gardening endeavours.

My bees were on the ivy… loads buzzing around in the drizzle, well I do live in England!!!

Yes, you will be weeks ahead of us here in the north, Pat. Nice image of bees on ivy in a drizzl!