What was your swarm season like? After a long cold spring, it started to warm up mid-May here in Nairnshire and all 8 colonies produced swarm cells in preparation for swarming by the end of May. June was unusually warm with lots of sunshine and a great nectar flow, but since the start of July it has rained nearly every day at some point. This blog opens with my swarm season and leads on to discuss the astounding behaviour and roles of nest-scout bees.

Swarm Control.

All 3 colonies in my out-apiary had their queens and a few frames of brood and stores removed in poly nucleus boxes to my home apiary. They are all queenright now but one small colony superseded its queen over winter and built up slowly in spring then prepared to swarm and produced a drone laying queen when I left them with a queen cell after taking away their queen. The new queen didn’t get mated for some reason so I united a nucleus from my home apiary to this colony using the newspaper method. I chose a queen that had headed up a colony with low varroa levels and no chalkbrood or signs of other diseases. It is very handy having lots of nuclei at this time of year and they are my insurance policies. It means that I never buy in queens.

Using Nuclei as a Management Tool.

I also use nuclei for boosting colonies that need brood if their queens have taken a long time to get mated and laying, or if I need a test frame of eggs to find out if there is a queen in a colony, or not. One such colony has just produced queen cells and so I have left them to make a new queen. Again, the queen that laid the eggs has been chosen carefully by me because of good traits Taking a frame here and there also reduces congestion in the nuclei which can get overcrowded and the wee colonies can swarm. At the end of the season when I am happy that all the colonies are queenright, I shall give away surplus queens and unite the bees to any less strong colonies.

I’ve collected 2 swarms from the out-apiary and the large one in the apple tree was opposite my three colonies and probably came from one of them if I missed a queen cell when checking a week on from removing the queen and nuc. I’ve never been able to confirm this because all the colonies, bar the small one with drone layer, have built up quickly again. I suspect they are from hive 9 because of their matching stripey yellow colour, and that swarms usually bivouac near the hive they swarmed from but you never truly know with bees unless you see things for yourself.

The second swarm in the out-apiary was small and opposite the 3 free-living nests in the chimneys of the old walled garden where fruit trees were once espaliered and warmed in spring by fires. It was in a gooseberry bush which was a lot easier to collect than it looks. I just pulled one prickly bunch of branches to the side with my hand, and trod the others with my left foot while juggling the poly nuc box underneath. The bees mostly all landed inside the box, including the queen, as luck would have it, and I took them home to nurture in the side apiary at home. I know that colonies have lived unmanaged for years in this wall and I am keen to study their behaviour and varroa coping strategies. This was probably a secondary swarm as it was small with a virgin queen that started laying 11 days later. They are dark greyish bees and only cover three brood frames now and are being fed fondant rather than syrup to reduce the risk of robbing. The wasps are out in full force already. I plan to overwinter this swarm in the poly hive which can be built up using spare deep brood boxes and shallow boxes for stores.

Beginner’s Luck.

Another swarm came from a nuc that was being used to raise a new queen from a second favourite colony. I had already used its original queen for a queenless colony but the nuc was robust enough to raise a good new queen because it had plenty of nurse bees and stores. I decided not to interfere with their choice of queen cells and, as the wee colony was spread over 2 5-frame brood boxes and a shallow super, I was not thinking about swarming. However, during a beginner class I was teaching one Sunday my students and I were returning to the garden from an out-apiary visit just in time to hear the roar and watch a wee swarm emerge from the nuc and settle in a conveniently low garden shrub. They had never seen a swarm before and it was the icing on the cake especially as they were hoping to take home a nucleus of bees. I scanned the swarm and saw the virgin queen walk on the surface briefly. I had several sightings before she came into view on a good spot for removing her safely by the wings without damage. Once she was safely inside a cage, I shook the swarm into a nuc box and placed the caged queen on the top bars and covered the nuc with a tea towel and opened the front entrance. Half an hour later all the bees were inside the box, apart from 3 or 4, and the lid was secured, entrance shut, and the nuc ready for transport to its new home in Keith.

I don’t have a lot of space in the home apiary so I did a Demaree swarm control on two colonies leaving them as vertical splits and ultimately a 2-queen system sharing shallow supers in the middle. The old queens of both colonies were placed on empty frames of drawn and undrawn foundation in the bottom brood boxes and the top brood boxes produced new queens which worked well initially. However, they were both difficult to manipulate and impossible to handle alone. What is disappointing is that both these colonies made second attempts at swarming from the bottom brood boxes leaving me with a lot more work than I’d bargained for. So, I’ve learned a good lesson and will not be repeating this method. Into the bargain, and much to the amusement of Gelda, one of these colonies swarmed at 12:30 one hot thundery day and took to the oak tree rather than the usual low shrubs (for the last 6 years, all swarms, that I know about, here have settled low down within easy reach). This one stayed for 3 hours only then took off with a great roar in a dark comet shape over the hedge and village in the direction of Nairn. I ran along the road behind them checking for signs of action around chimneys but they disappeared into thin air!

Swarm Behaviour.

A friend commented on the fact that over 5 years 90% of swarms in his apiary settled about 8 feet up in the same tree. He pondered on the fact that swarms mostly settle or bivouac near the parent hive that they have just erupted from, and mostly make their choice of new home from there, but not always as we will discover. Is this because the scouts measure up the size of the swarm and compare it with the size of the potential new home? Professor Tom Seeley doesn’t think so, and he shares some astounding things about scout bees and their remarkably adaptable behaviour around finding nest sites that he has discovered since writing Honeybee Democracy in a BeeCraft article1.

Younger Workers Swarm.

The average prime swarm contains about 10, 000 honey bees, or about 2/3 of the colony. Younger workers tend to leave with a swarm and up to 70% of workers less than 10 days old leave with it2. It is advantageous to have younger workers establish the new nest because they are going to live longer and can produce wax for new comb right away.

We know that only a few hundred workers become nest-site scout bees and that they can go out searching for a new home a week before the swarm issues. Until recently, we thought that the choice of nest site was made only after the swarm left the hive and clustered in the bivouac position, but elaborate work by Professor Seeley and colleagues shows how a swarm can miss a step in the process and fly directly to the new nest site. How many swarms have left our hives that we have no idea about?

Scout Bees.

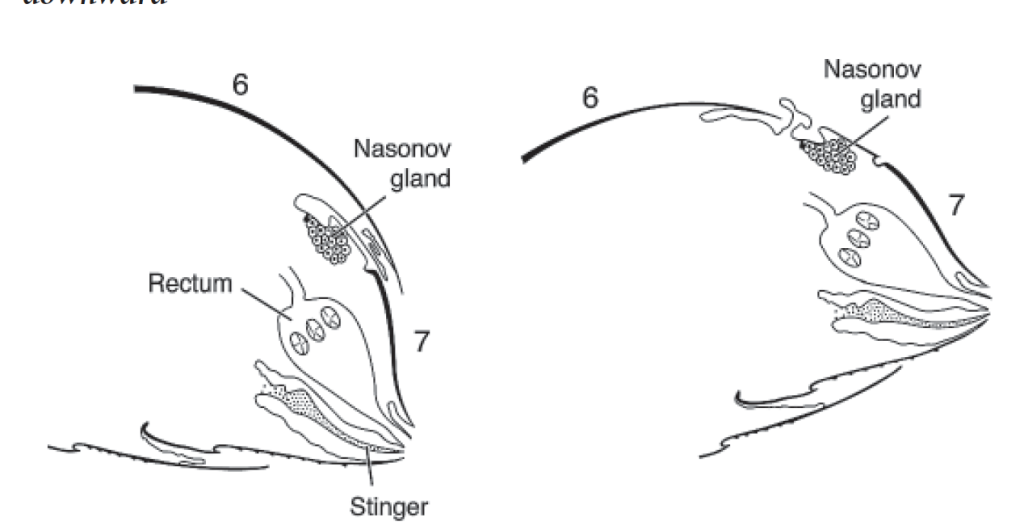

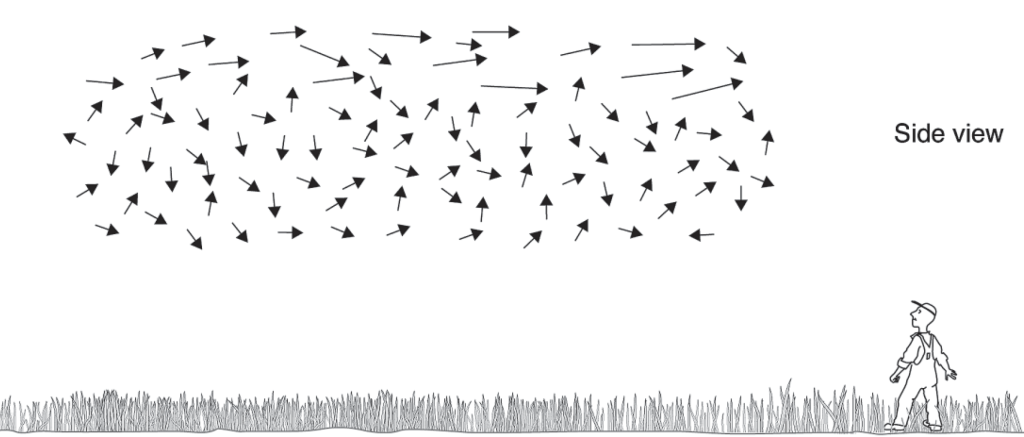

When a swarm leaves for the new nest only about 300 to 400 scouts in 10, 000 bees have any knowledge of where they must go. These scouts perform many roles within the actual swarm cluster. If the swarm is not flying directly from the hive to the new home, scouts go off from the bivouac site to explore 30 square miles of surrounding country looking for the ideal home of 40 litres capacity, south facing, several feet off the ground, and with a small entrance. Back on the swarm they perform the waggle dance and the swarm makes a collective decision about where to go. In order to fly, flight muscles must warm to 35˚C and several dozen scout or activator bees walk slowly over the combs producing the worker-piping signal. To make this sound, one of the activator bees presses her thorax down on another bee for around one second which produces a vibration of about 250 Hz which sounds to us like a brief shrill whine. When flight muscles are warmed and the bees ready for take-off, scout bees (activators) scuttle over the combs buzzing their wings and bumping into other bees producing a “get going” signal or the buzz-run. The buzz-run signal also triggers the tumultuous exit from the hive of the swarm.

Swarm Flight Guidance.

If only 3-4% of the swarm have ever visited the new nest site how does the swarm find its way there? One might think that it is guided by Nasonov pheromones that play a role in orientation and are often referred to as the “come hither” scent often seen at the hive entrance when a swarm has just been hived and the workers are calling in their nest mates to the new home. However, this is not the case as Beekman and colleagues discovered in 20063. An elegant experiment in which every worker bee in a study of three swarms, had her Nasonov gland sealed shut with paint proved that the swarms were not guided by this scent. It was needed at the new nest entrance but not during flight. Back in 1955, Professor Martin Lindauer reported noticing several hundred bees shooting through the tops of swarms looking like they were guiding them. Later with the invention of new technology, Lindauer’s hypothesis was tested using harmonic radar to track the flight path of individual scouts. Time consuming analysis of these recordings proved that these streaker bees were indeed guiding the swarm. Scout bees may be small in numbers but they are big on action.

References.

Seeley, T,D,. (2021), The Astonishing Behavioural Versatility of Nest-Site Scouts, BeeCraft May 2021, pp 9-11.

Winston, M.L, . (1987) The Biology of the Honey Bee, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Seeley, T, & Chilcott. A,. (2015) The Flight Guidance Mechanisms of Honey Bee Swarms, BeeCraft April 2015. Vol 97, No 4, pp 7-11.

The height of the hives leaves me with a arm that’s just not up to lifting. Good to see pictures and your spot on was the flow strong this year and did you get any Heather honey?

Hello Rick. Thank you for commenting.The lifting was a bit much but I am not sorry to have experimented with this method. I am glad that I didn’t harvest all the spring honey as we are experiencing an unusually cold and wet July with days when there will be no nectar secretion or foraging. The bees have plenty stores left and I have had a small harvest which keeps my local honey customers happy. The ling heather (Calluna vulgaris) starts flowering around now and into August, so no heather honey yet. I don’t take my colonies to the moors but they can access heather from both my apiaries though the crop is not pure heather. That suits me fine and the bees don’t have to travel.Ann.

Great to hear about your free-living bees in the area. That’s where varroa resistance often starts – good luck!

I have a few bait hives a small distance away from the apiary. Scouts at the entrances are the early signs that one of the hives are making vacation plans.

Fascinating to learn about “Streaker” bees leading the swarm. Thank you Ann

Hello Steve. Thank you for responding and offering advice. I am very excited about finally getting my hands on a free-living colony having been trying since 2019! Ann.

Hello Ann. The wild colonies living within the stone walls around your out-apiary offer a great opportunity to monitor wild-colony persistence over the years. Many folks think that wild (aka “free living”) colonies are short lived, but I have found otherwise and wonder if it is the same for these colonies.

The monitoring process is simple: 3 times a year (early spring, mid summer, and autumn) check each site for bees flying in bearing loads of pollen. If you see this, then you know that the site is occupied by a colony that is alive and rearing brood. Keep records in a notebook.

I check the wild colonies that I monitor in late April (before swarm season), late July (after swarm season) and late September (end of summer). If you can do this for three years, starting this July, then you will collect some important information. Just a suggestion, of course. –Tom

Hello Tom. Thank you for commenting and suggesting the monitoring. I have been doing this for the past year and will continue with it. The owner of the property was picking fruit near the wall on Saturday and saw another swarm emerge from the wall and settle high in a walnut tree. It was still there yesterday (Monday) which was dry unlike showery Sunday. There is a bait hive not too far away but I am not holding out much hope of attracting it now.Ann.