This week, it stopped raining and a couple of dry sunny days made the land much less soggy. Thousands of grey lag geese (Anser anser) stopped off in nearby fields of barley stubble to pick up grain left behind after harvesting. They take to the air on my approach, even from a distance of several hundred yards. I hear whirring wings on the still air, even above the cacophony of their gregarious chatter.

The dry days have been prefect for long walks, but sometimes the light is so poor I don’t bother to bring my camera. Of course, these are the days when something exciting happens and I regret my decision. Like today when I hear a bumble bee and find a large queen Bombus terrestris collecting orange pollen on gorse, Ulex europa. I’m amazed at this on December 16th, even though the temperature is around 10 degrees Celsius. I expected her to be tucked up in her winter nest for one. I also a miss capturing the image of a robin posing for the perfect Christmas snap on a red and white sign. He stands perfectly still as I pass by within a couple of feet. Then a red squirrel bounds out of the woods ahead of me and runs up the road stopping to drink from a puddle before scaling a large oak tree just over the dyke!!

Candle-Making.

Connie and I get down to some serious candle making and produce 2 large rolled candles and some small moulded ones for the Christmas tree. We melt some lovely yellow bees wax in the bain Marie and pour it into a baking tray on top of non-stick paper. When it’s solid, but still warm, a couple of minutes later we cut the sheet in half. It is rather thick but we are proud of our first attempt and Connie manages to roll the first piece around the wick as it is still malleable. The second piece I warm with the hair dryer as Connie rolls. She stands on a small step ladder to reach the work surface.

The ultimate test is whether the large candle burns well or not so we light it and sit down to enjoy our ritual cup of mint tea from the garden, and oatcakes liberally covered in honey. It burns perfectly.

Varroa: Reproduction.

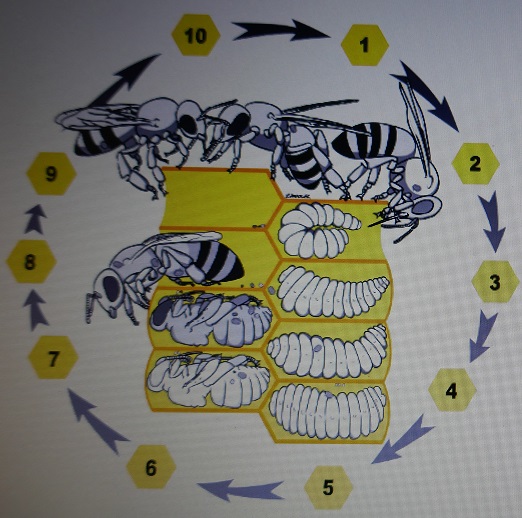

During the phoretic stage (1), as described in last week’s blog, the varroa leaves the cell riding on a newly emerging bee, or imago. She then finds an older nurse bee, around 12-14 days of age, to hang around on until she finds the perfect cell to enter and lay her eggs (2). During the active season when brood is present, she will spend an around 4-5 days living in this phoretic stage. What attracts her to the cell, and how does she know to enter one just about to be capped? Well, the brood gives off very attractive chemical pheromones. Actually, in this case they are called kairomones because they are attractive to another species. Pheromones attract same species animals.

This female mite is usually referred to as the foundress mite and she prefers drone brood because she has a better chance of reproducing there because drone cells are capped for around 15 days compared with around 12 days in worker bees. Varroa will also reproduce in worker cells, but knowing the preference for drone cells gives us a slight advantage when it comes to management of varroa. Some people think that the size of the cell impacts varroa reproduction and that small cell foundation is an effective tool to use against the mite. However, research by Seeley et al (2010) proves otherwise (see below)

Entering the Cell.

(3) The foundress enters her chosen cell and and finds her way to the bottom. Remember that she is blind and finds her way by following the chemical signposts. Until the cell is sealed, the mite is underneath the larva amongst the brood food. So how does she breathe?

Amazingly, she is fitted with 2 snorkel-like breathing tubes called peritremes. These are situated on her anterior (front) lateral aspects near her 3rd and 4th pairs of legs. As soon as the cell is sealed there is no time to be lost and she attaches to the bee pupa (4) and starts feeding by first wounding her host and keeping this feed hole open thus allowing infection and viruses to enter. After a good feed of fat body tissue with its rich source of vitellogenin, egg production can begin. The first egg is usually laid around 70 hours after cell sealing (5). This is always an unfertilized egg producing a male. Like honey bees, varroa have a haplodiploid system whereby females have 32 chromosomes (diploid) and males have just 16 (haploid).

After laying this first egg, another is laid 30 hours later and it will be female. The male takes 5-6 days to develop from egg to adult whereas the female takes 6-7 days. This means that once the male is mature he only has to wait 20 hours for his sister to be ready to mate. Only one male is produced which allows the number of reproductive females to be increased. Unlike honey bees who undergo complete metamorphosis, varroa mites emerge from the egg in the juvenile form of the adult, similar in looks but immature. These stages are called the protonymph and deutonymph which you can see below.

The Offspring.

At regular 30 hours intervals the foundress lays a female egg until she has produced around 5-6 eggs. These offspring hatch and and mature and feed on the same larva from which they obtain nutrients and viruses (6). They share the latter later with other bees. As the mites mature they mate with their brother within the cell (7). When the honey bee imago emerges from the cell the foundress mite and her mature female offspring leave on this bee (8). The male and any immature females remain in the cell and die there (9) to be cleaned up later by a house bee. So, the male spends his life inside the cell. Mites emerging from the cells don’t hang around for long before finding a new host bee (10) and so the cycle continues. However, they must have mated before leaving the cell otherwise they remain sterile.

By the way, mite faeces may be seen on the underside cell walls when you are inspecting combs during a diseases inspection. They show up as white debris.

More next week.

This is a beautifully illustrated and clearly described account of Varroa reproduction. Good work! It is great, too, to see you small, smiley, beeswax candlemaker friend.

Thank you, Tom, for appreciating and endorsing the content.

Brilliant reading Ann. I am very proud I have done my Oxalic trickle start to finish by myself due to the current situation. I hope an pray they make it through the winter.

Thank you, and well done you, Sarah. Trickling is a lot easier and safer to do on your own. I am sure that your bees will come through just fine. The critical time for them is Feb/March when the queen is getting up to speed with egg laying and the stores are reducing. I’m sure you have fondant on hand? If you can’t get hold of any I can post some up as my bee shed work shelf is buckling under the weight of the stuff! I hope things are ok in the north and you are not working too hard. Say a big hello to Max for me.