“Beekeeping today is still as it has always been: the exploitation of colonies of a wild insect; the best beekeeping is the ability to exploit them and at the same time to interfere as little as possible with their natural propensities.” Leslie Bailey, Honey Bee Pathology, 1981

Bees in the wild generally choose tree homes that have a capacity of around 40-80 litres, are 3 m or more off the ground, and have a south facing entrance of between 10-40 sq. cm which makes them easier to defend against predators (Seeley 2010). This tells us that, amongst other features for a dream home, bees like a small entrance to defend, see wild bee tree below.

We know that bees can live in almost any cavity, provided it can be kept dry and well- defended, but that beekeepers manage them in specifically designed hives to monitor for disease and successfully harvest honey. So how, and what should we should choose to house our bees in? Well, to some extent this will depend on the race, or subspecies, of bee that we have, and whether we are hobbyists or bee farmers producing large amounts of honey.

Classification System.

To help us understand the races of bee we can refer to the Linnaean classification system of living things as devised by Swedish botanist Carl von Linne´ during the eighteenth century. Taxonomy is the science of identifying animal and plant life and arranging them into related groups. It involves the principle of using two Latinised names (binomial system). The first scientists used Latin which remains relevant today as the universal language amongst those who study life. For example, where I live in the Scottish Highlands, my bees collect nectar from the prolific plant above that we call ragwort. However, in another region of the UK it might be called mare’s fart, or stinking Willie. How confusing is that. But if we use the internationally recognised naming system for this plant in the asteraceae family and call it Senecio jacobaea then we all know which plant we are talking about. By the way, we think ragwort reached Scotland in the 1700’s carried in the hay brought north by the Duke of Cumberland’s army and named stinking Willie after the much-hated general. Any organism named under this system is written in italics, and the first letter of the first word is always in capital. For example, Apis mellifera is the Western honey bee, and Apis mellifera ligustica tells us that the subspecies is the Italian ligustica bee.

Honey Bee Species.

All honey bees are members of the genus Apis and are subdivided into species of which there are only a few and possibly only six or more living species of Apis (Seeley 1985). In Asia, the giant honey bees Apis dorsata can be found, and in Europe the Western honey bee Apis mellifera (A.m.) resides. There are around 30 subspecies of A.m. that live within the species’ original range of Europe, Western Asia and Africa (Ruttner 1988).

The Italian subspecies, Apis mellifera ligustica, has certain characteristics such as; light tan/golden colouring, prolific breeding and good honey producers in good weather. They tend to be gentle bees so are easy to manage but they produce large colonies and need plenty of hive space if swarming is to be prevented. Because they continue to raise brood long after most other types stop brood raising before winter, these bees need more winter stores and often starve over winter in poorly managed apiaries. This is a very good bee for Italian conditions.

Knowing the life history informs us that Italian bees need to be kept in hives with large capacity and that they may not produce much honey in areas where the weather is poor such as in the north of Scotland. They produce lots of brood well into the autumn which means that they don’t generally store enough food for winter. So, if they are to survive a harsh winter, the beekeeper must supplement the honey stores by feeding the bees with a sugar syrup.

The dark European bee, Apis mellifera mellifera (A.m.m.) (see above) has characteristics that makes it ideal for colder climes, for example; longer abdominal hair (twice the length of warm climate bees); winters well on low stores; thrifty and able to obtain honey crop regularly in poor summers; slow build up in spring but ready for the heather crop at the end of summer; not a prolific bee, and has a low population. These bees can be kept in smaller hives, they may require less feeding, and usually survive winters well.

Local Bees.

Until 1919, A.m.m. was probably the commonest honey bee in the UK, and was often kept in 10- framed double walled hives called WBCs after inventor, William Broughton Carr. This hive was ideal for the size of the brood nest. The “Isle of Wight disease” (Now thought to have been caused by chronic bee paralysis virus rather than acarine disease) struck in that year and the honey bee populations in the UK crashed necessitating the importation of bees from abroad. This impacted hugely on the gene pool in the UK and also meant that colonies were not genetically adapted to their new locations. We now know that importing queens and moving colonies over large distances forces them to live in areas where they are poorly suited and this may affect their health. Recent studies conducted in Europe found that colonies with queens of local origin lived longer than those with non-local queens (Büchler et al.2014).

The key to choosing bees is to go for local bees though this usually means that you don’t have much choice of bee subspecies. Most of our bees are hybrids or mongrels and all of mine certainly are but they are adapted to live here and fly at lower temperaratures than bees from other regions.

Choosing Hives.

The choice of hive is best based on what your local beekeeper friends use in relation to bee type commonly kept. If you go out and buy the first hive you take a fancy to and find it wrong for your needs it is a costly mistake. Many beekeepers don’t consider buying second hand hives, and certainly not frames, because of the disease risk. American foulbrood spores can lurk in the woodwork for over forty years and affected colonies are by law destroyed in the UK.

There is an enormous choice since the recent introduction of high- density polystyrene hives which are a cheaper option and provide greater thermal insulation for colonies in winter than thin wooden hives. They also aid colony thermoregulation in summer. They are lighter to manipulate for beekeepers working alone. For the traditionalists and environmentalists who love wood, red cedar is good because it doesn’t require painting and it develops a beautiful silvery patina over time. Some choose to nourish the wood with non-toxic oils such as linseed. It is worth mentioning here that the thermal properties of wooden hives in the UK deteriorated around the time of WW2 when wood was scarce and hives were made from thinner less dense wood. This is partly why poly hives are so popular now and some beekeepers claim that colonies overwinter better in them than uninsulated wooden hives.

I use a mixture of wooden and poly hives and I always insulate the space below the roof with natural sheep’s wool over winter.

The British National Hive.

The British National hive is very popular but requires two brood boxes for prolific colonies, though using larger capacity 14″ x 12″ (jumbo) brood boxes can reduce the number of frames to be checked during a hive inspection. The downside is the heavy weight of full boxes, and the individual frames when handling jumbo frames. The Commercial and Langstroth hives were designed with brood box capacity similar to the jumbo framed National hives, and these are popular amongst commercial beekeepers. The Langstroth is the most commonly used hive worldwide.

For beekeepers keen to keep bees closest to how they live in the wild, tree hives, top bar and Warre´ hives can work well for them but the frames must be moveable and available for inspection by Government Bee Inspectors in the UK as part our legal responsibility to monitor and control foulbrood diseases. If you start off with hives similar to what your mentor is using it will probably be much easier for you to learn the art and craft of beekeeping and make decisions later about what is best for you and your bees. There are more hive designs available than ever before but whatever you choose bear in mind that it is easier if all your hives are the same type and interchangeable.

Meet The Cast.

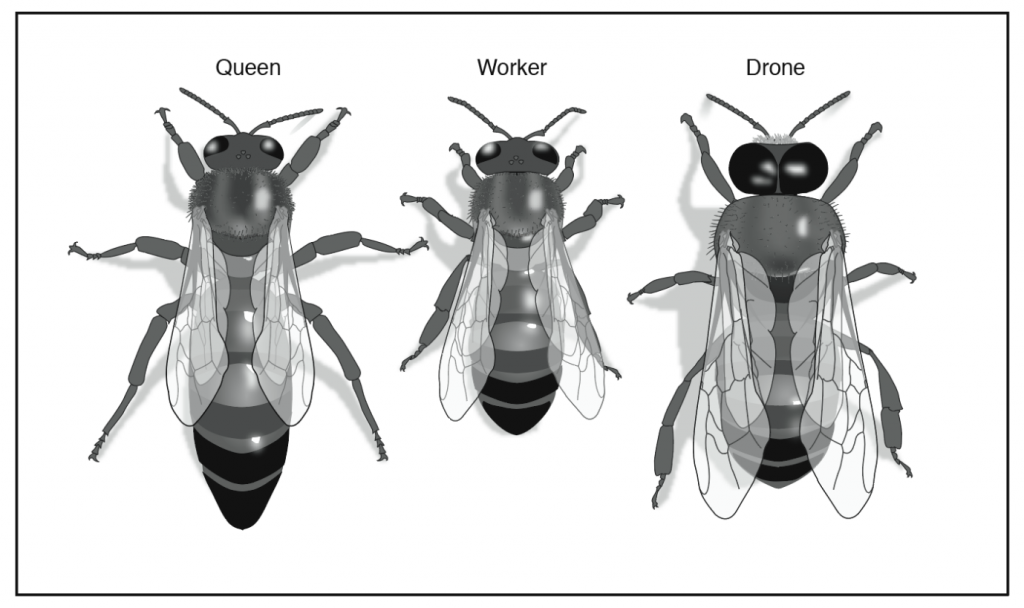

There are two sexes of honey bee—male and female, and two female castes—queen and worker. You might encounter conflicting information around the 2 female castes statement. Scientifically it refers to age- related tasks undertaken inside the hive and the drone is not included because he has no inside roles. His only purpose, mating and passing on genes, is carried on outside the hive.

The Leading Lady.

Let’s examine the inhabitants of the hive. Enter the queen—centre stage— mother of all the bees in the colony. She has a longer more pointed abdomen because, after her mating flights, her role is egg laying and her abdomen is full of reproductive organs and eggs. Eggs are laid at a rate of around 1,500 –2,000 eggs a day. Compared with a worker bee, the queen has longer legs and a shorter curved sting. The latter is primarily used to kill rival queens, though a friend was stung by a queen while he was marking several one afternoon. She didn’t die because her sting is shaped differently from a worker’s. She must have recognised the other queen pheromones on his hands. She can live for up to four to five years, but only if she still has adequate amounts of semen stored to fertilise eggs and maintain sufficient bee numbers in the colony.

Don’t think for a minute that the queen actively rules the colony for she is but only one part of this amazing insect family which functions as a superorganism. An individual bee cannot survive alone for long, and the collective activities of all the bees enables coherent colony function. Queen pheromones are powerful chemical messages signalling to the workers that she is there and that all is well. If the colony gets overcrowded, and the message fails to get around all the workers, they may make swarm preparations. When this happens queen cells are made to provide a new replacement queen. The queen is then denied food to slim her down and enable her to fly off with them to a new home. The colony make her leave the hive by pushing her around and head- butting her. I’ve watched a swarm leave a hive and seen the queen on the landing board attempt to go back inside only to come out again seconds later amidst a wave of excited bees.

Pheromones govern other activities within the colony, such as brood pheromones instructing nurse bees to feed the larvae brood food and then, just before the cell is capped over with wax while the larvae pupate, a different brood pheromone alerts the nurse bee that the larva no longer requires feeding.

The Worker Bee.

The worker is the smallest bee, and has a sting that is normally left behind in the non-bee victim’s skin because of the depth of penetration, and the barbs. The main visible difference is the pair of pollen baskets (corbiculae) on her hind legs which neither the queen nor drone has. She makes brood food in the hypopharyngeal, and mandibular glands in her head. She has four pairs of wax gland on her underside that secrete small scales of transparent beeswax resembling sea salt flakes. She manipulates these with her mandibles to construct hexagonal wax cells. Her ovaries are underdeveloped though she can lay eggs if the colony becomes queenless, but the eggs can never be fertilised and so the colony will die out unless the beekeeper re-queens it.

Age Related Tasks.

The worker progresses through a series of age-related tasks (age polyethism) depending on when various glands mature. As soon as the new worker emerges, she cleans the cell out after herself, but she cannot feed the queen, or the larvae, till her hypopharyngeal glands mature a day or so later.

During the summer, worker bees live on average six weeks and the first three are usually spent on indoor tasks. If there is a shortage of foragers, house bees can mature earlier and, if there is a shortage of house bees, foragers can revert back to performing former indoor duties.

The following is the ordered list of duties: cell cleaning; capping brood; tending brood; queen tending; receiving nectar; handling pollen; comb building; cleaning hive debris, ventilating the hive by moving wings; resting; guard duties (sting gland mature); first orientation flight, first foraging trip. Then there is continued collection of nectar, pollen, propolis and water until the death of the worker around three weeks, or 800 miles–a return flight from Aberdeen to London. There are many variables affecting the lives of workers including weather, pesticides, predators (swallows and blue tits enjoy snacking on bees) and accidents such as chilling and dying when water collecting.

Meet The Drone.

Drones are the beefy boys with bullet-shaped abdomens, and two enormous compound eyes for spotting the queen on mating flights. Their antennae (used for navigation and scent detection) are a segment longer than those of the worker. They have neither sting nor pollen baskets. Their chief role is to pass on genes and mate with the queen–a torrid affair after which the drone’s penis turns inside out and he falls dead to earth.

However, don’t be fooled into thinking that the stay-at-home drones are lazy good-for- nothings. It’s true that most are turned out of the hive at the end of summer, but that’s because drones eat a lot and a colony would be unlikely to survive winter with them around. Drones produce 50% more heat than workers, so in cold summer weather they probably contribute significantly to colony thermoregulation.

Producing drones is costly for a colony because they require more food than workers, and larger cells, so be mindful when culling drones as a means of varroa control. Varroa prefer to breed in drone cells due to them taking longer to develop than the female castes and some beekeepers manipulate drone production to reduce varroa populations.

Honey bees are protandrous meaning that the males mature before the queens in spring so when you first see drones flying in spring you should be thinking ahead to swarm season. The peak of drone rearing occurs around four weeks before swarming.

The number of drones in a colony depends on several factors including; the size, and race of colony, the amount of constructed drone comb, whether the colony has overwintered or has newly formed from a swarm, and so there may be between 300—3,000 drones.

Life History & Development.

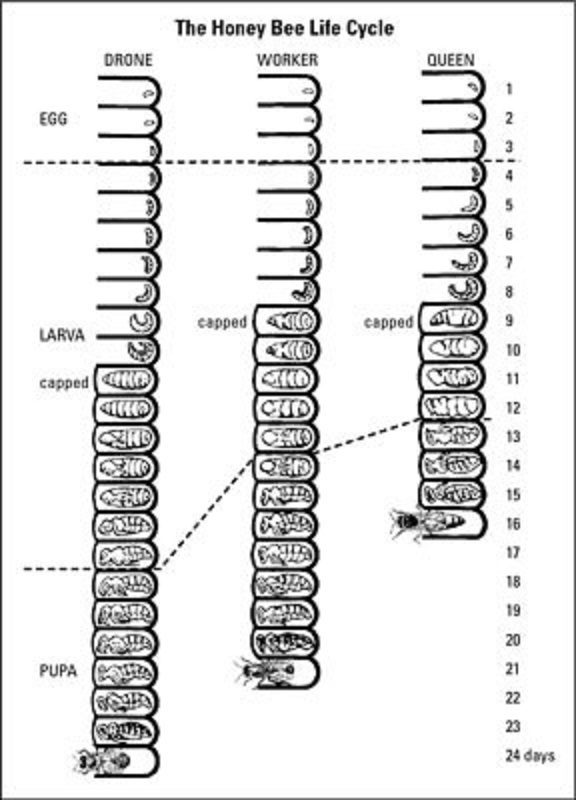

To better understand colony dynamics, and “read” a colony, having the basic knowledge of the honey bee life cycle is key. There are four distinct phases: egg; larva; pupa; adult bee. The queen takes 16 days (“Sweet sixteen”) to develop from egg to adult, with the cell being capped in wax on day 8. The worker (“key to the door”) takes 21 days with cell capping on day 9, while the drone takes 24 days from egg to emergence “Drones on for longer”—and his cell is capped on day 10. You need to know this information for many management situations, but when it comes to swarm season, it is essential knowledge. A swarm usually departs from the hive around day 8 when the first queen cell is capped with wax so you need to take preventative swarm control measures early on. You can only find out this information by doing weekly inspections during swarm season.

Royal Jelly.

All three types of bee receive royal jelly for the first two larval days then, as the third day progresses, larvae destined to be queens continue on royal jelly while the drone and worker larvae are fed a diet of honey water and pollens called bee bread. Bee bread contains P-coumaric acid which shrinks worker ovaries and helps select the worker caste. It is the lack of this substance in royal jelly, along with genetic programming, that makes the queen so different.

The eggs are white and minute with a poppy seed shape. Each one has an opening on the broader side for the sperm to penetrate. The queen sizes up the cells with her antennae and when she reaches a larger cell, which will cradle the drone, she lays an unfertilised egg and so the drone is created by parthenogenesis. He has 16 chromosomes which is half the number of queen and worker bee. The drones have a mother and a grandfather, but no father.

When a worker bee is created, as the queen lays an egg, she releases semen from her spermatheca (storage chamber) to fertilise the egg. If a queen is to be produced the workers create a special cell called a queen cell that hangs down from the comb with intricate sculpturing resembling a peanut Pupae in the cells are positioned with heads towards the exit for an easy debut. The middle photo shows white fat healthy c-shaped larvae just before the capping stage.

The queen is in the larval stage for around 8 days then her cell becomes capped with wax. She then pupates during which time her body tissue and cells undergo massive reorganisation so that she can emerge around day 16. She takes around 4-5 days to fully mature and be ready for her orientation flight, and then her several mating flights. She is shamelessly promiscuous and mates with between 7-17 different drones which should provide all the semen for the rest of her reproductive life. She will remain in the hive unless she leaves with a swarm. Mating with so many drones, from various colonies, in a special area known as a drone congregation area some miles from her hive, ensures genetic diversity and that she doesn’t mate with drones from her own colony.

The worker cell is capped around day 9 and she emerges around day 21. The drone cell is capped at day 10 and he emerges around day 24, becoming sexually mature 10 days later. He will live for around 3—4 weeks, spending 2-3 of those flying out to drone congregation areas on fine days looking for sex.

If you want to be truly amazed, watch photographer, Anand Varma’s, “The First 21 Days of a Bee’s Life” film made for National Geographic. This shows in detail developmental life within the cell. Please note that when this film was made, we thought that varroa fed on the haemolymph (bee blood) but new research shows that it is far more serious a problem with varroa feeding on fat body tissue which is analogous to our liver. https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=anand+varma+honey+bee+development&qpvt=anand+varma+honey+bee+development&view=detail&mid=DE875A4911C3BC893831DE875A4911C3BC893831&&FORM=VRDGAR&ru=%2Fvideos%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Danand%2Bvarma%2Bhoney%2Bbee%2Bdevelopment%26qpvt%3Danand%2Bvarma%2Bhoney%2Bbee%2Bdevelopment%26FORM%3DVDRE

References:

Büchler, R, C. Costa, F. Hatjina et al.2014. The influence of genetic origin and its interaction with environmental effects on the survival of Apis mellifera L. colonies in Europe. Journal of Apiculture Research 53:205-214.

Davis, C. 2014.The Honey Bee Inside Out, BeeCraft.

Ruttner, F. 1988. Biogeography and Taxonomy of Honeybees. Springer Verlag, Berlin

Seeley, T. D. 2010. Honeybee Democracy, Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

Seeley, T. D. 1985. Honeybee Ecology, Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

Varma, A. 2015, The First 21 Days of a Bee’s Life, National Geographic, TED.Com: YouTube.

Winston, M. 1987. The Biology of the Honey Bee, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.