Introduction.

It’s hard to believe that this is the last blog for March and it’s officially spring next week here in the northern hemisphere. Beekeepers from all over the UK have been sitting exams this month, and I’ve been completely taken up with a close family bereavement and all the practical and legal aspects involved with the process of sorting belongings and selling a house. I’m home at last and watching the bees bringing in basket loads of yellow willow pollen. There’s a big tree just along the road, and when I walk outside the garden I see bees zipping past on the fly ways to this fabulous pollen source. More about this tree later.

When I need to relax, I often pull down a flower book from the shelf and just look at the pictures. This lovely book landed on my doormat at the beginning of the month and I’ve been itching to read it. It deals with some of the most important topics of the day and I highly recommend it to you.

Book Review.

Title: Where do the bees go? An exploration of key UK forage species for pollinators

Author: Lesley Jacques

Publisher: Northern Bee Books, 2025

ISBN: 978-1-914934-95-7

Paperback, A4, 112 pages

Cost: £20

Available: Northern Bee Books and other book shops

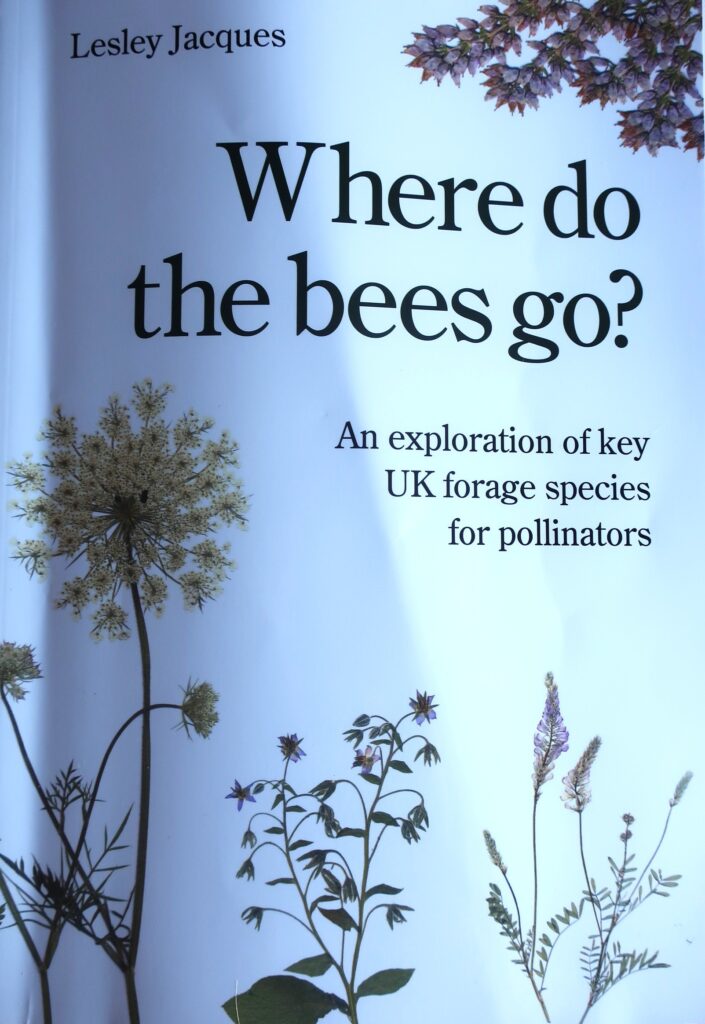

Where do the bees go? An exploration of key UK forage species for pollinators by Lesley Jacques is a detailed guide to 24 of the key UK families of important pollinator plants for bees. Jacques is a scientist by profession with a special interest in biology and botany relating to beekeeping. She is a Master Beekeeper and was inspired to compile this plant portfolio while studying for the National Diploma in Beekeeping which is unique to the UK.

What makes this publication stand out from similar beekeeping books is the attention to detail and its timely focus on all UK bee pollinators which are currently under threat from climate change, habitat loss, disease, and pesticides. It is a beautifully illustrated book and the pressed flower photographs are superb. The author has painstakingly and skillfully collected and preserved an elaborate herbarium, and photographed pollen grains from each collected plant.

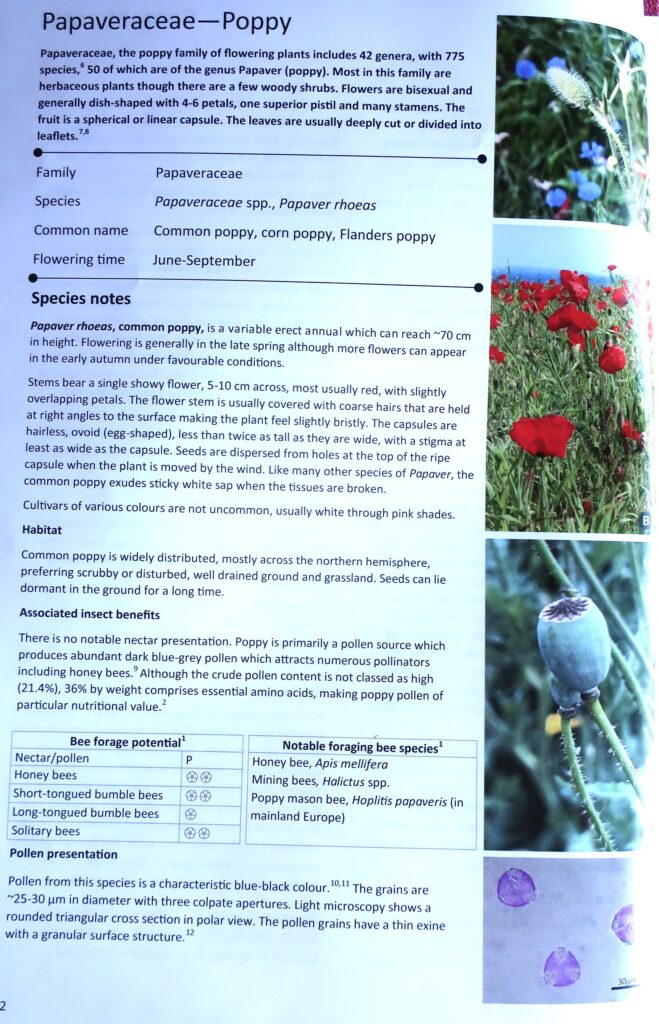

The book is written in a field guide format though its A4 size probably restricts its use to indoors. We find information relating to each plant family including the number of genera and species, and features such as leaf shape, petal numbers, fruit type, flowering times and habitat. The most valuable information for the beekeeper or conservationist relates to the food value of each plant which is reflected in its nectar and pollen production. The protein value of each pollen is explained and shown as a crude protein level. We learn that plants whose pollen falls in the crude protein range of above 25% are considered to be of most value to foragers. The other key features are bee forage potential, and notable foraging bee species which are shown in tabulated form. We learn whether a particular plant produces pollen, nectar, or both, and if it is of value to honey bees, long-tongued or short-tongues bumble bees, or solitary bees. The different foraging bees are listed by both common and binomial names.

Some families contain more useful plants than others and here the pea family (Fabaceae) section, for example, features five important plants all with similarly sized and shaped pollen grains and crude protein values.

A contents page to help the reader navigate the book, and an extensive reference list contribute to the value of this book for beekeepers and beekeeping students with impending examinations. However, the readership of this informative and topical book will be wide-ranging—farmers, botanists, conservationists, gardeners, research scientists and many others will find this a very useful book.

Making Your Own Forage Journal.

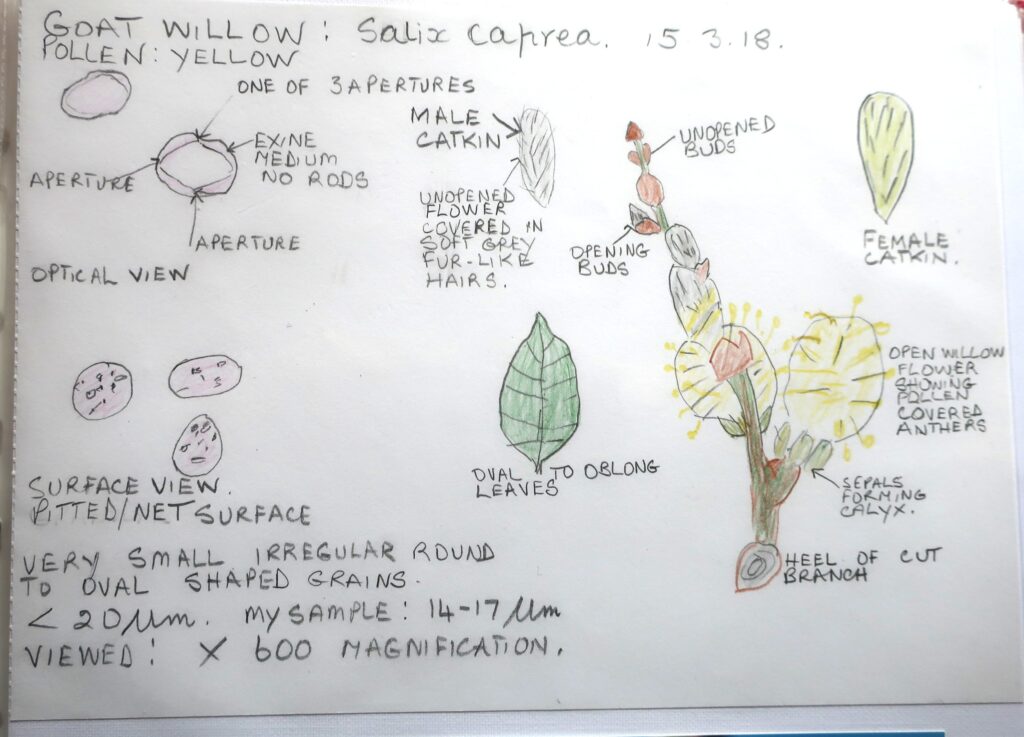

You can easily compile your own forage diary and plant profile for reference. It is also an excellent teaching tool for new beekeepers in your area. You can start with a simple journal of what you see the bees foraging on locally. You can use Lesley Jacque’s book as a guide to the usefulness of each plant you find. Depending on your microscopy skills, you can study the pollen grains and identify pollen loads coming into the hive, or analyse honey samples when your expertise develops.

I made a simple forage journal a few years ago and here is a snapshot of my favourite spring pollen source, willow.

Plant common name: Goat Willow

Latin name: Salix caprea

Common family name: Willow

Scientific family name: Salicaceae

Plant height: varies according to species (1-60+ feet) Goat willow around 30 feet

Flowering period: February to May according to species and district. Mid to late March-May in Nairnshire

Provides: early pollen by male flowers only. Nectar by both flowers under very favourable conditions not often available in Nairnshire

Utilised by: queen bumble bees of many species, and honey bees in Nairnshire. In the south of England, mining bees also take advantage of willow

Honey crop: no

Willow

“The feathers of the willow

Are half of them grown yellow

Above the swelling stream…”

By Richard Watson Dixon

Goat willow is just one of over 300 members of the Salicaceae family, which include poplars, in the northern hemisphere. Willow is known also as sally, sallow, and pussy willow, the latter being named for the fur like quality of the coverings before flowering. There are around 20 wild species in the UK.

Willow thrives in damp soil and near rivers and its flexibility makes it ideal for basket weaving. In some parts of the country the bark was chewed to relieve headaches, and modern asprin’s main ingredient, salicylic acid, was originally isolated from willow bark before its synthetic manufacture today. The tannin-rich bark can also be used for curing leather.

Being a dioecious plant, whereby male and female catkins are produced on separate plants, and pollen is secreted by male flowers only, willow reduces the risk of self-pollination. I know this because I once planted a female willow that produced no pollen and I puzzled over this till I discovered why. Both male and female flowers produce nectar under certain conditions, but not often in Nairnshire where it is usually too cold at flowering time. Male catkins are grey whilst female catkins are green and slightly longer.

If the pollen from the male part falls onto the female part of the same plant causing fertilisation, then genetic diversity is reduced and inbreeding may occur. This is one plant strategy adopted to ensure cross-pollination with another plant of the same species.

Willow is easy to cultivate by placing cuttings in water till the root system sprouts. This is how my willow tree originated—in my bee buddy Cynthia’s vase of daffodils that she was given when she fell in the garden and broke her shoulder. The willow stems were left to root on the window ledge long after the daffodils withered.

Beekeepers could plant an array of different willows providing valuable sources of protein and lipid-rich pollen over a long period from late winter through to late spring. Crude protein levels are above average at 22%.

Pollen under microscope (x 600 magnification)

Colour: yellow

Shape: irregularly round to oval

Size: very small grains under 20µm, specimens viewed were 14-17 µm

Exine features: medium with no rods

Surface: net/pitted

Number of apertures: 3

Aperture type/ furrows: furrows with pores though none seen in these specimens

Other features: Oily pollenkitt which is a good source of lipids.

I have to agree this book is both beautiful and useful.

Hello Helen. Thank you for contributing and commenting. It is a great addition to our libraries.

Thanks for this interesting post. I am sorry to hear about your bereavement. I know from personal experience how difficult these events can be emotionally, together with all the legal and practical issues that arise.

I enjoyed your book review and your own personal pollinator analysis of willow. Here at present, one of the main sources of interest are the clumps of lungwort and comfrey which seem to be the favoured plant of the hairy-footed flower bee (Anthophora plumipes). These bees are wonderful to watch in early spring with lungwort in particular attracting this species over the many other flowers available.

Thank you, Philip. I have never seen a hairy-footed flower bee. Lucky you.