June Roundup.

Welcome to all new Beelistener readers and subscribers, and thank you to everyone who contributed blogs, and generously donated towards the maintenance and security of the website. Without your support Beelistener would cease to exist.

Swarm Season.

We reach the end of a fairly dry and warm month here near the Moray Firth and I have never heard of so many local swarms before. Worryingly, there have been numerous calls from anxious homeowners reporting bees taking up residence in house spaces at an unprecidented level. Judging from letters to the main UK newspapers, this is happening all over the UK and it begs the question; are more poorly prepared beekeepers than ever taking up the craft? The local professional bee remover has been worked off his feet this season.

My own bees have given me a run for my money with the two earlier shook-swarmed colonies building up to swarm preparation this week. All 8 nuclei are full and doing their jobs. After our local association summer BBQ on June 10th, I went down to my out apiary to do a swarm patrol which involves searching in all the apple trees for the tell tale signs. The sun was still high and warm and golden sunlight filtering through the foliage lit up thousands of bee wings massing round the biggest swarm I’d clapped eyes on in a while. I wished I had taken up Cynthia’s offer to come with me.

I did have a bee suit but no wellies. I grabbed the white sheet and skep from the car, and the poly bait hive from the far end of the apiary. I surveyed the scene before making my move. I knelt down with the nuc on my left knee and stretched my right arm up to grasp the branch and pull down. Most of the bees landed in the nuc which became incredibly heavy but some landed on my sandaled feet and stung like fury. Several found their way up my legs and zapped me good and proper. However, my goal was to get the nuc secured and home so I ignored the pain and persevered but ended up with a pulled chest muscle which is only getting better after 17 days. I did go to bed early that night because my feet and ankles were swollen and it was bliss to put them up!

I suspected that this swarm came from a shirty big colony that always went for us the moment we set foot in the apiary, and was expecting that the nucleus method of swarm control hadn’t worked and that I would find a virgin queen in the swarm. However, I was pleasantly surprised to find a lovely big mated dark unmarked queen and concluded that the swarm must have errupted from one of the free-living nests in the wall nearby. Back in the day when fruit trees were espaliered to the wall, the gardener lit fires in several wall chimneys to warm them up and three colonies have taken up residence here. The big grumpy colony is settled now with a new and large yellow queen and the big swarm is thriving in the home apiary.

Nailing Frames.

Are you involved with teaching new beekeepers? It is easy to assume that making up frames is clear and simple for everyone but it is not always so and this needs some attention in first lessons. Can you see the problem in the photo above?

I knew I was in for trouble when I spotted this in a hive belonging to a beekeeper who needed help checking for swarming signs during a busy week when they couldn’t check on the bees.

How many nails do you put in frames? Some people use 11, but I put 9 in Hoffman’s self-spacing frames, and 11 in non-self-spaced frames.

Bumble Bees.

Are you bewildered by the number of different, yet very similar looking, bumble bees around your garden or local park? Identifying them can be challenging but good fun and knowing more about them can help preserve them, so let’s look at their life cycle this week.

Confounding identification is the fact that there are around 250 species of bee in the UK including the honey bee, 24 species of bumblebees, and 225 species of solitary bees. If that’s not enough, some cuckoo bees masquerade as bumblebees killing their queens, usurping their nests and fooling their workers into raising cuckoo bee offspring as their own. Some hoverfly species impersonate wasps and honey bees so all is not always as it seems in the insect world.

Bumble bees are large fuzzy insects closely related to honey bees and they share the following scientific classifications: Class: insects; Order: hymenoptera (membrane- winged); Family: apidae. However, honey bees are in the Genus Apis whereas bumble bees are in the Genus Bombus. Using the Latinised scientific binomial classification system avoids further confusion given that one bumblebee, Bombus terrestris, is known by several common names around the country including Large Earth Humble-bee, Buff-tailed Humble-bee and Buff-tailed Bumble bee.

Bumble bees look like big friendly teddy bears with their round fluffy bodies covered in soft hairs called setae that pick-up pollen. However, most bumble bee species have pollen baskets on their legs. Cuckoo bumble bees are the exception because they steal the food of others and so don’t need shopping baskets.

You might almost imagine friendly bumble bees rolling over defencelessly on their backs like dogs wanting to be tickled. However, the brightly coloured body bands that help us identify bumble bees also serve to scare off animals. This is known as aposematism and functions as a warning to predators, so a brightly coloured ball of bees might scare off marauding predators such as birds. Female bumble bees have a painful sting which I know all about because I once rescued a distressed bee in a tissue at work because I didn’t have a glass handy. The buzzing against the window was distracting and I didn’t think it through before acting swiftly. Ouch!

Bumble bee sub-species have varying lengths of tongues ranging from 7.1mm in B. pratorum to 13.5 mm in B. hortorum which means that they can access flowers with differing lengths of tubes leading to the nectaries. Some short-tongued bumble bees tear holes in the base of the flower to rob nectar and honey bees sometimes take advantage of this strategy to help themselves. Bell heather is a good example and if you look closely at the bell of this flower, which is made up of 9 fused petals, you might see the tell-tale holes. Honey bees can access the nectar by probing inside the flower but they find it so much easier to steal instead like their bumble bee counterparts.

The proboscis (mouthparts) is hard, long, tapered and designed to fold away neatly and invisibly under the neck when not in use. When in use it forms a straw-like structure where fluid is lapped up and rises in the tube in a capillary-like action. Interestingly, honey bees have very similarly structured proboscises but just slightly shorter and their lengths range across the sub-species from 5.7-6.4mm in the British Black Bee (Apis mellifera mellifera) to 6.4- 6.8mm in the Carniolan Bee (Apis mellifera carnica).

Social Insects.

True bumble bees, also known as social insects, have pollen baskets (at least the two female castes do) which distinguishes them from kleptoparasitic cuckoo bumblebees who have none but mimic bumble bees in order to steal their nests and resources. Social insects have a dominant and reproductive female called the queen, and another female caste called the worker whose sole function is to forage and feed the colony. Social insects care for their offspring in colonies. Males are produced later in the season with mating and passing on their genes being their main functions. However, there is great competition and usually only 1 in 7 males successfully mates with a queen. The queen usually mates with only one male unlike the honey bee queen that can have between 7-17 successful suitors.

When males emerge from their natal cells, they spend only a few days in the nest where they do no work at all. They then go off and forage for themselves and can often be seen sheltering from rain under a flower head where they may also have sleep-overs when darkness falls. Unlike honey bee males, bumble bee males do not die during mating. They use a scented attractant pheromone to lure the female to a rock or piece of ground and mating may last from 10-80 minutes, usually taking place on or near floor level unlike airborne honey bee mating. After inserting sperm into the female genital opening the male will follow this with a sticky material that hardens to plug the opening preventing other males from mating for at least three days. This strategy ensures that his genes are passed on successfully.

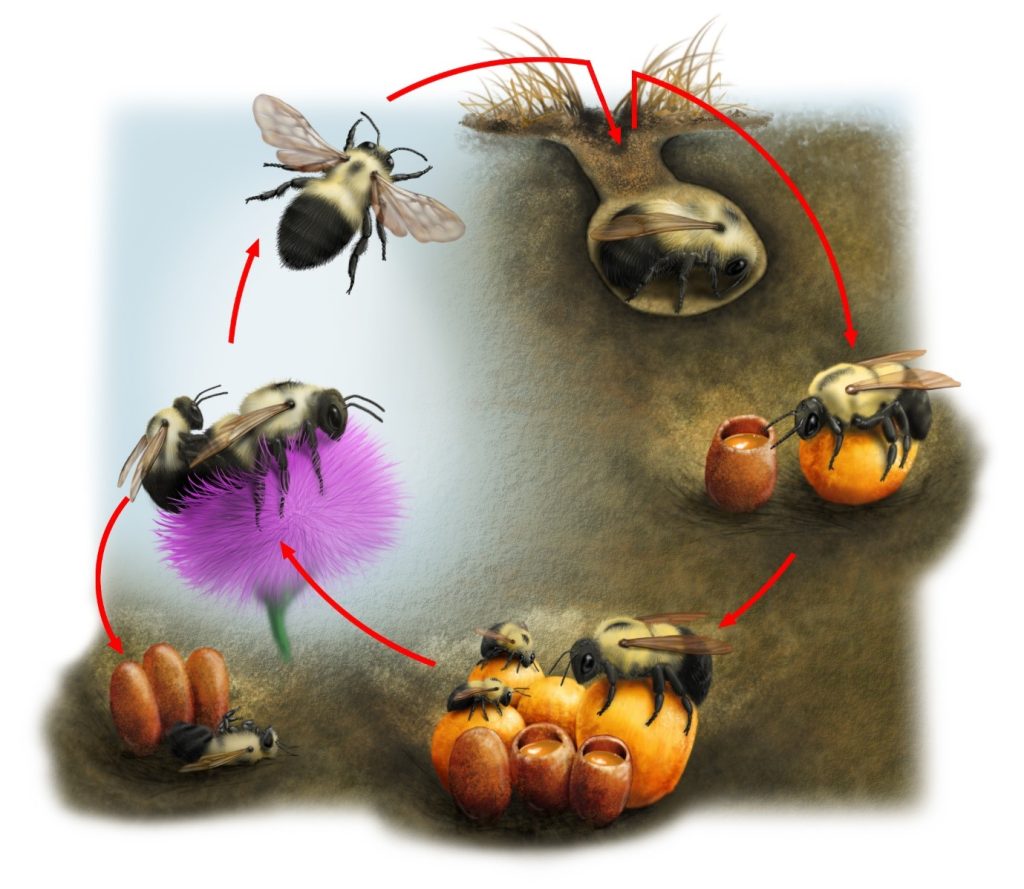

The illustration shows a native North American bee life cycle the stages of which are relevant to bumble bees, (from top right going anticlockwise) :

- The queen bumble bee at the of summer finding an underground cavity where she will overwinter by herself, the males and female workers having all died off after fulfilling their roles during one short season.

- The fertilised queen emerging during spring when her first responsibility is to replenish her own depleted body through adequate nutrition. Over winter hibernation she has lost most of her body fats and so soon as possible must collect pollen to restore protein levels needed for tissue growth, especially for her developing ovaries. Nectar collection ensures that she has enough energy and minerals to function efficiently. Bumble bee queens differ from honey bee queens in that the latter have no pollen baskets and don’t forage.

- The queen finding a suitable nest and stocking the larder with honey pots. The spring nest site is crucial and it must be well insulated and cosy. Old mouse nests are ideal homes and they can be above ground surface or below depending on the species of bee. Once satisfied with her new home the queen secretes wax from the wax glands on her underside and forms little honey pots which she will fill with nectar to sustain her as she lays eggs and incubates them, and perhaps during some harsh spring weather when confined indoors. She then collects pollen and forms a large lump not much bigger than her own body. On this bed she lays a few eggs which will hatch into larvae to become the first workers. To speed up the development process the queen lies over the pollen bed to incubate her brood. If heat is needed, she isometrically contracts her flight muscles to generate more heat and every so often she leans over and sips from the honey pots gaining calories and energy to fuel this process. Like honey bee larvae, bumblebee larvae undergo a few moults then develop a silken cocoon and progress through a pupation period. When the first workers emerge from their cocoons it takes around 24 hours for their wings to harden and then they go straight on outdoors to foraging duties, unlike the honey bee that spends three weeks indoors on household duties before foraging.

- The male emerging and mating as previously described which completes the life cycle at the end of summer as males, female workers and old queens die leaving only newly mated queens to begin hibernation and start the new cycle of bumble bee life.

Loads of swarms on the south coast of England too. Have you come across a newly mated queen from an artificial swarm producing swarm cells (not emergency or supersedure) within a week of emergence and going off with the swarm? In 20 years I have never had that, cannot find reference in books/web. Thought they were OK for a few weeks when I found eggs, 20 days later there was a new virgin, several emerged swarm cells present and 60% of the bees in a massive colony gone.They had plenty of space for brood and honey so not congested. Love your blog!

Hello Amanda and thank you for sharing your experience with us on swarming virgin queens. I am also glad that you enjoy the blog which I enjoy writing for people like you who appreciate it. I have not had the same experience exactly but I gave a colony plenty of room and did a version of a Demaree. The old queen in the bottom brood box had plenty of room but still decided to make swarm prep some weeks later. Very stong urges to reproduce.I bet there will be other people with stories like yours as it seems to have been the swarmiest season across the UK. A shame about your honey crop after all the hard work you did to control swarming.

Fascinating as always Ann and such a detailed and interesting description of the bumble bee’s life. Also I agree about the rise in swarming in peoples chimneys. It did become quite a trend to get bees and for some it didn’t last and it is probably those that are causing the problems. Bee keeping takes time and dedication.

Thank you for commenting, Susan, and I am glad you enjoyed the life history.

No need to be bamboozled by bumblebees!The Bumblebee Conservation Trust offers a complete introduction and ID guide to the UK`s bumblebee population,written by Dr Nikki Gamans,Dr Richard Comont ,SC Morgan and Gill Perkins.pub 2018 by the Bumblebee Conservation Trust.A major difference with honeybees is also “buzz pollination”

which pollinates tomatoes and other soft fruits.

Ann gives a good description of the bumblebee life cycle,but the illustration cycle is not of a native bumblebee,there are no black and white bees,and is more like a (solitary) Ashy Mining bee,andrena cineraria! I have personally seen a small number of

Bombus terrestris (buff tailed) mating and flying in the air,but at low altitudes compared to honeybees.

This is also Solitary Bee Week 2023 for the 240 other bee species….

Thank for commenting, Gelda, and for adding good information from your own wide experience of bumble bees. Perhaps you might treat readers to a guest blog on bumble bees?

Yes..topic under consideration!