A honey bee colony builds its nest mostly of beeswax, a material that worker bees produce themselves, but a colony also uses a material that the workers collect from the environment: resins. These are sticky substances that are secreted from various places on plants, but especially from leaf buds on deciduous trees and wounds on coniferous trees. I have enjoyed watching bees collect light-yellow resin from the leaf buds of an eastern cottonwood tree (Populus deltoides) that grows near one of my apiaries (Fig. 1). Trees secrete resins to defend themselves from herbivores, bacteria, and fungi, so it is not surprising that resins are laden with chemical compounds that are distasteful to herbivores and toxic to bacteria and fungi.

Sometimes the words “resin” and “propolis” are used interchangeably, but this is a mistake. The word “resin,” like the words “nectar” and “pollen,” is a botanical term. The word “propolis” is a beekeeping term. It was coined by writers in Ancient Greece: pro (in front of, or at the entrance of) and polis (city or community). Bees make propolis by mixing resin with beeswax; its composition is 50-80% resin, and 20-50% beeswax. I suppose bees do this mixing because it saves on resin collection. Perhaps, too, the bees find it easier to “handle” propolis than straight resin.

Fig. 1. A resin collector with a shiny load of resin on the corbicula (“pollen basket”) of her left hind leg. This bee’s resin load will be nibbled off by resin-user bees when she gets home.

Colonies varnish the smooth surfaces inside their homes with thin coatings of resin. Also, where there are rough surfaces or undesired openings, colonies will coat or fill them propolis. They do so to foster colony health. Studies by Professor Marla Spivak at the University of Minnesota have found that colonies living in hives whose inner surfaces are coated with propolis, relative to colonies living in hives without propolis coatings, have healthier workers and higher survival.

A second reason for propolis work is to make a colony’s nest cavity snug. Where I live (in Ithaca, New York), I see bees collecting resin and working propolis mostly in late summer and early fall. This is when my bees are filling cracks in my hives, sealing tight their covers, and building walls to shrink their entrances (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. This hive’s entrance was reduced in late summer by bees that built a propolis curtain across most of it, leaving only two small openings. Each one was just large enough for 2-3 bees to squeeze through it simultaneously.

How does a resin collector sense her colony’s need for more resin? Does she do so directly, by noting the ease (or difficulty) of finding places that need to be sealed up? Or does she do so indirectly, by noting how quickly her resin loads are removed from her hind legs by her hive mates? A rapid removal might indicate a high need. It is possible, too, that a resin collector pays attention to both of these variables.

These questions were tackled in the summer of 2002, by Professor Jun Nakamura, a professor at Tamagawa University in Japan, when he came to Cornell University during a sabbatical leave. Jun and I set up an observation hive colony and then Jun put paint marks (for individual identification) on 102 resin collectors in this colony of about 3,500 bees. He then patiently observed and video recorded the behavior of these resin collectors inside his hive (Fig. 3). From time to time he boosted the study colony’s need for resin by removing the observation hive’s glass walls and removing whatever propolis the bees had collected to seal these glass walls to the hive’s wooden frame.

Fig. 3. Professor Jun Nakamura video recording a resin collector in his observation hive.

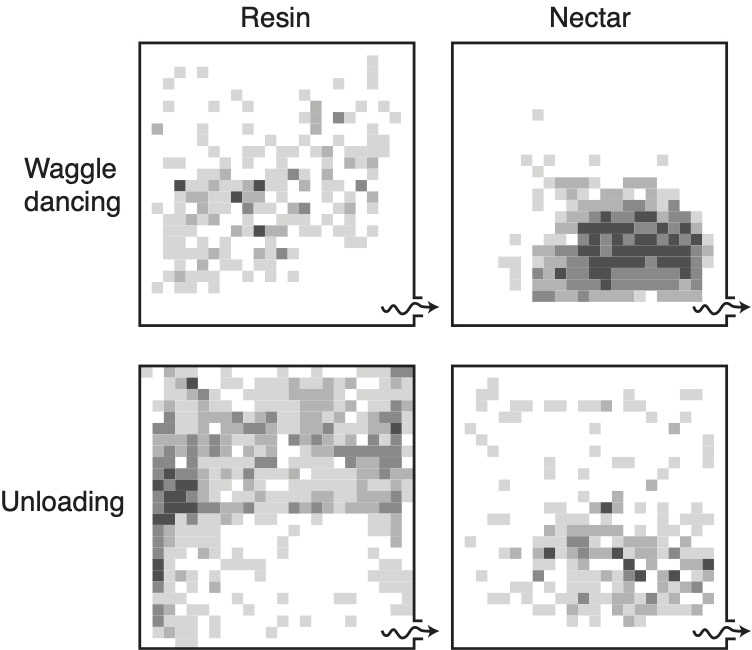

Jun observed that when a resin collector gets home, she walks deep inside her colony’s nest (Fig. 4), to wherever resin users are working, and that she gets unloaded slowly and by multiple resin users. Each resin user chews off just a small chunk of a resin collector’s two loads. By walking to a site where resin users are working, a resin collector minimizes the amount of walking that the resin users must do to get their snippets of resin. And this helps to minimize the energy expended by the resin users to process a resin collector’s load. In contrast, a nectar collector usually gets unloaded just inside the hive’s entrance (and usually by a single nectar receiver). This makes sense. If a nectar collector were to walk up to the combs where nectar receivers are storing nectar, she would not spare several receiver bees from making trips down to the nectar unloading area.

Fig. 4. Spatial distributions of the locations of waggle dancing and unloading, for resin collectors and nectar collectors, in a two-frame observation hive.

Jun also learned that many of the resin collectors also functioned as resin users: 16 (21%) were seen caulking, 7 (9%) were seen scraping wax with their mandibles to get wax to mix with resin for caulking, 6 (8%) were seen taking resin from a fellow resin collector, and 6 (8%) were seen examining crevices with their antennae (a key part of the caulking process). We concluded that resin collectors have many opportunities to sense their colony’s need for resin directly.

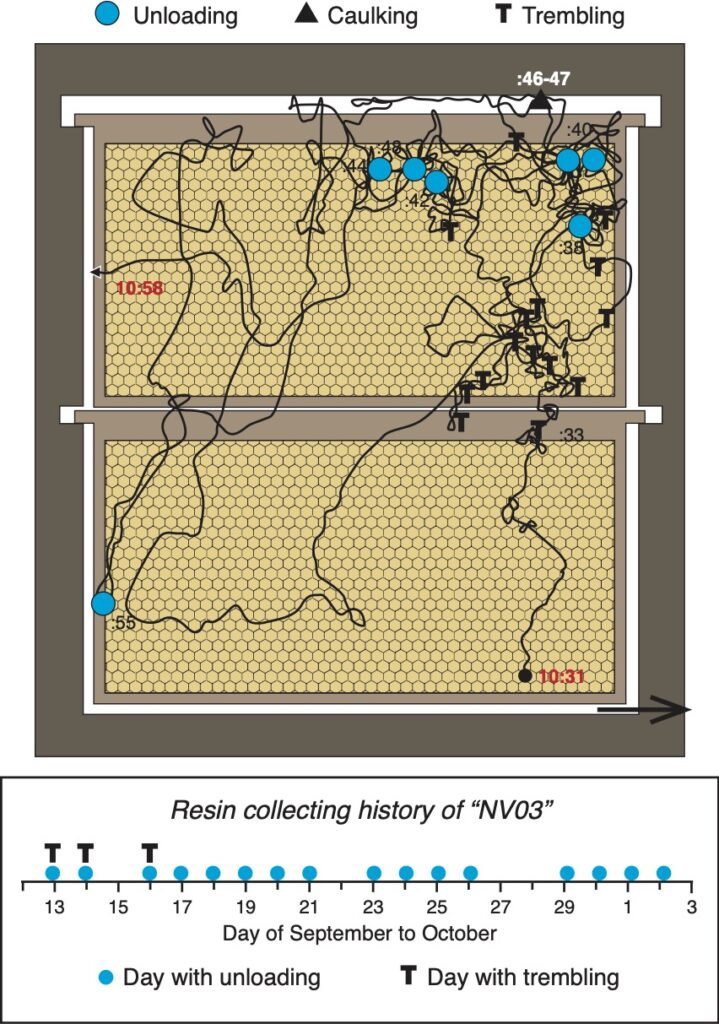

This conclusion is supported by what we observed in the video recordings that Jun made of the in-hive behavior of 35 resin collectors. Each recording began when a labeled resin collector scurried into the observation hive. We saw that a resin collector, unlike a nectar collector, does not remain just inside the hive’s entrance when she gets home. Instead, she walks to a site in the hive where propolis is being used for caulking. This is depicted in Fig. 5, which shows the in-hive actions of the resin collector NV03 on the morning of the second day of her work as a resin collector. She entered the hive at 10:31 and then she walked to the top of the hive, where bees were sealing the hive’s glass wall to its wooden frame. This resin collector’s first unloading occurred at 10:38, seven minutes after she arrived home. Then, between 10:40 and 10:55 she made more 6 pauses to get unloaded, and one pause to do caulking, before she walked to the other side of the hive, at 10:58. Between 10:31 (arrival home) and 10:38 (first unloading), she often performed tremble dances. Probably, these were calls to be unloaded.

Fig. 5. Top Pathway of resin collector NV03 during the first 27 minutes of a return home on the second day of her work as a resin collector (September 14). Arrow at bottom right indicates the hive’s entrance/exit. Bottom Record of NV03’s work as a resin collector on 17 days, from 13 September to 2 October.

A second important thing that we saw in our video recordings of 35 resin collectors was that 5 of these bees came home carrying both a chunk of resin in her mandibles and two balls of resin on her corbiculae. Each of these five bees began caulking with the resin in her mouthparts as soon as she came to a spot in the hive where caulking was being performed. So, here, too, we saw several resin workers functioning as both a collector and a user. The story was only slightly different for the other 30 resin collectors that carried home their resin loads entirely in their corbiculae. A sizable fraction (36%) of these resin collectors engaged in caulking after their resin loads had been plucked, bit by bit, from their hind legs.

These observations revealed that resin collectors might get information about their colony’s need for resin both directly (by sensing places that need to be caulked) and indirectly (by sensing how long it takes to get unloaded). The stage is now set for conducting experimental tests of these two hypotheses for how the work of a colony’s cadre of resin collectors is regulated.