Introduction.

I hope that the nectar has been flowing and the bees have been doing tremble dances in your neck of the woods. I was pleasantly surprised to harvest nearly 60 lbs of mostly lime blossom (basswood, linden) from a couple of colonies in the back garden. The temperature didn’t get much above the low twenties but obviously it was warm and humid enough for the lime flowers to secrete nectar this year.

I want to welcome all our new subscribers who joined this month, and to everyone who generously donated towards the maintenance and security of the website. I really appreciate all the support in the form of guest blogs too. Please keep them coming as the readers enjoy a change of topic and style. This week, Professor Tom Seeley has generously contributed another fascinating story about bee behaviour and given us a peep into his latest book, Piping Hot Bees & Boisterous Buzz Runners. Thank you, Tom.

der Zittertanz.

In 1923, when Karl von Frisch published his first detailed report on the dances of honey bees, he described not only the waggle dance, but also a second dance that he called (in German) der Zittertanz. In English, it is usually called the tremble dance. He described this dance in as follows:

“At times one sees a strange behavior by bees that have returned home from a sugar water feeder or other goal. It is as if they had suddenly acquired the disease St. Vitus’s dance [chorea]. While they run about the combs in an irregular manner and with slow tempo, their bodies, as a result of quivering movements of the legs, constantly make trembling movements forward and backward, and right and left.”

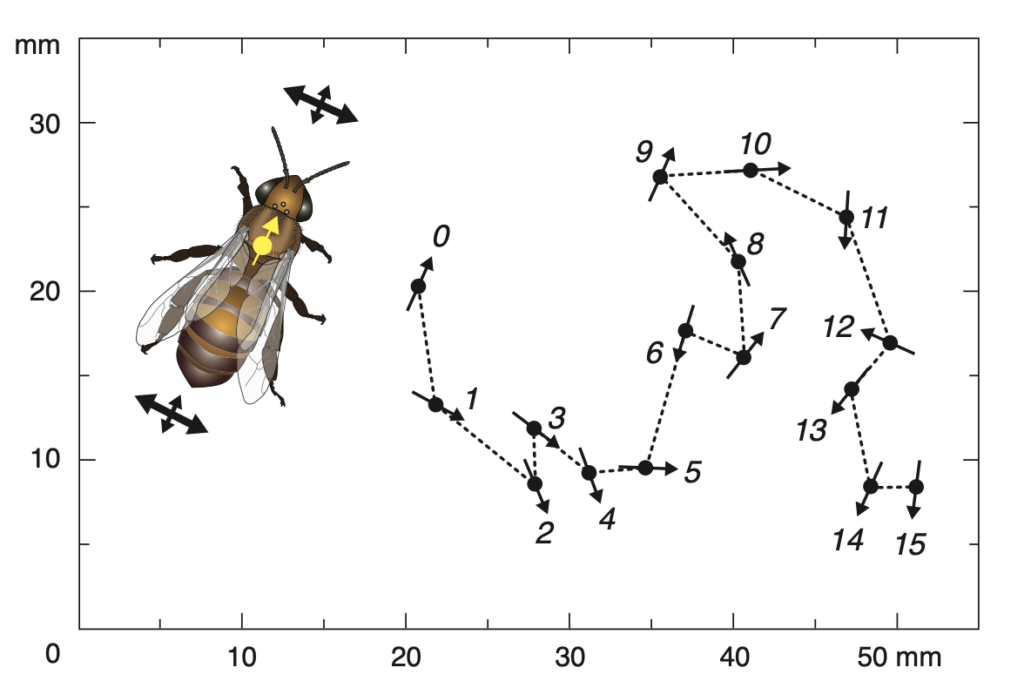

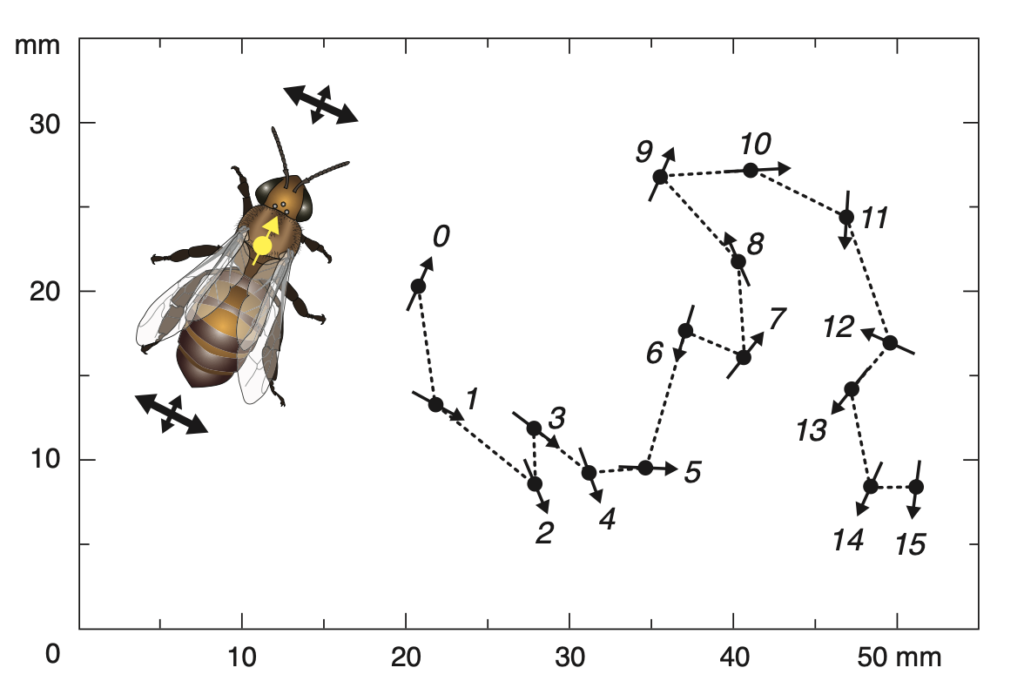

The “strange behavior” described by Karl von Frisch is depicted in Fig. 1. We see that a bee performing the tremble dance moves her body in three ways, and all at the same time: (1) vibrational—she jiggles her body side to side; (2) rotational—every second or so, she changes the direction that her head is pointing; and (3) translational—she walks slowly across the comb. When you first see a bee walking around on a comb performing the tremble dance, you might suspect that there is something seriously wrong with her, for it looks like her nervous system is malfunctioning. Is she suffering from pesticide poisoning? I discovered, however, that actually she is producing a signal that helps her colony take full advantage of a strong nectar flow.

Fig. 1. A 15-second record of a worker bee’s behavior while she performed the tremble dance on a comb inside an observation hive. The drawing on the left illustrates the eye-catching side-to-side movements (trembles) of a tremble dancer’s body, while the track on the right shows how this bee walked slowly across the vertical comb and rotated her body-axis by 30-90° every second or so. Note: 50 mm is approximately 2 inches.

Nectar Collection.

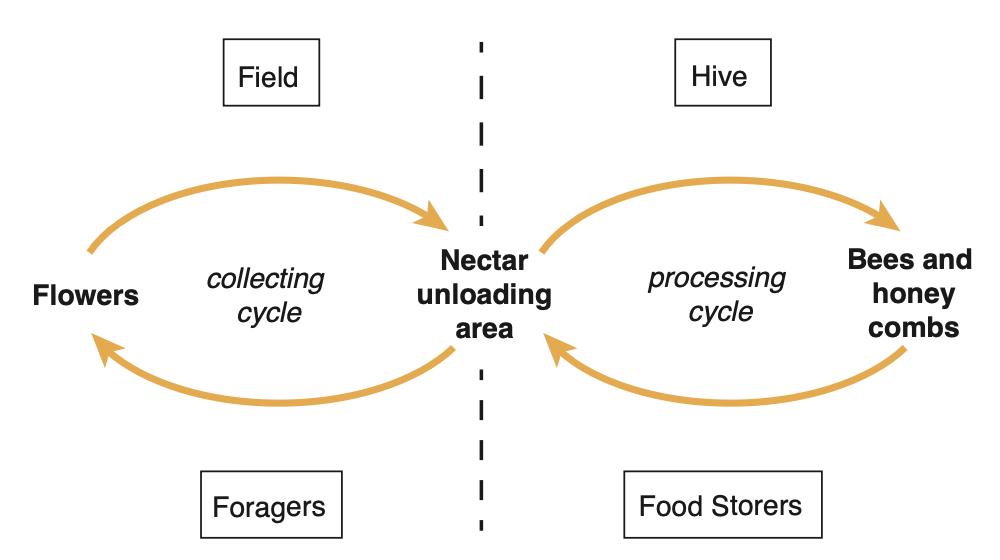

In 1987, I was studying how a nectar collector senses her colony’s rate of nectar intake, and so knows how strongly she should advertise her nectar source. I knew that when her colony’s rate of nectar intake is low, she is more inclined to produce a waggle dance than when this rate is high, but I did not know how she senses her colony’s rate of nectar intake. Fig. 2 shows the division of labor between workers that collect nectar and those that receive it and convert it to honey.

Fig. 2. The division of labor between nectar collectors and nectar receivers in honey bee colonies.

The Goal.

My goal was to find out if it is a long in-hive search time to find a nectar receiver that informs a nectar collector that her colony has a high rate of nectar intake. (I knew that I can tell whether the customer traffic in a grocery store is high or low by noting if the time to reach a cashier is long or short.) So, I performed an experiment in which I removed most of a colony’s nectar receivers, and thereby induced long search times for this colony’s nectar collectors. Then I watched to see if this manipulation discouraged the nectar collectors in this colony from performing waggle dances,.

The “trick” of removing most of the nectar receivers in my study colony, which was living in a glass-walled observation hive, increased the search times of the nectar collectors in this colony. But it did not increase the level of either the nectar-collector traffic into this colony’s hive or the aroma of fresh nectar inside it’s hive. So neither a high level of nectar-collector traffic nor a high level of nectar aroma could underlie whatever changes that I might see in the behavior of the nectar collectors in my study colony.

Feeding Station.

My helpers and I began our experiment by training a handful of nectar collectors from the study colony to visit a feeding station (Fig. 3) located 1400 feet (430 meters) from this colony’s home in the observation hive. This feeding station was the only good source of “nectar” for the study colony. It provided a rich (65% by weight) sucrose solution ad libitum. Every bee that visited the feeding station was given paint marks for individual identification.

Figure 3. An assistant, Oliver Habicht, tending the sugar-water feeder (sitting on the small table) that was visited by nectar collectors from the study colony.

The experiment unfolded over a four-day stretch of good weather: 14, 15, 16, and 17 July 1987. On each day, I allowed 15 bees to forage at the sugar-water feeder that was tended by an assistant. I sat beside the observation hive. When a labeled nectar collector arrived home and scrambled into the observation hive, I tracked her and recorded how long she searched to find a nectar receiver and whether or not she performed a waggle dance. On 14 July, I watched 68 return visits to the hive by the 15 labeled nectar collectors in my study colony. I saw that their search times were short: on average, just 11 seconds. I also saw that these bees performed waggle dances during 73% of their returns to the observation hive.

Over the next two days, 15 and 16 July, I continued to allow 15 labeled nectar collectors to make trips to the sugar-water feeder. Also, I spent each day daubing a dot of lavender-color paint on the thorax of every bee that I saw unloading any of the 15 bees returning from the sugar-water feeder. And, at the end of the day, on both 15 and 16 July, I opened the observation hive and plucked from its combs all the lavender-dotted bees (i.e., many of the colony’s nectar-receiver bees) and I put these bees in a small cage that was equipped with a sugar-water feeder. I needed these bees to stay alive and healthy. Over these two days (15 and 16 July), I labeled and removed from the study colony 482 nectar-receiver bees. This was ca. 12% of the colony’s members.

On the morning of the fourth day (17 July), the weather was sunny and warm—hurray!— and I began watching the bees in the observation hive, to see how the 15 nectar collectors that were visiting the feeder would behave when they returned home. Relative to the first morning in this experiment (14 July), would these bees find it harder to find nectar receivers and would they be less motivated to perform waggle dances, even though natural forage remained sparse and the feeder still provided rich sugar syrup?

As soon as these 15 nectar collectors resumed their work, I began mine. I repeated what I had done on 14 July. Specifically, I recorded two crucial things for each labeled bee (nectar collector) when she entered the hive: (1) how long it took her to find a nectar receiver, and (2) whether or not she performed a waggle dance. Soon, I saw that my removal of nectar receivers from the colony was having strong effects on the nectar collectors. Now, when the these bees returned home, they searched twice as long as before to find a nectar receiver (average, 21 seconds instead of 11 seconds). Also, they performed almost no waggle dances.

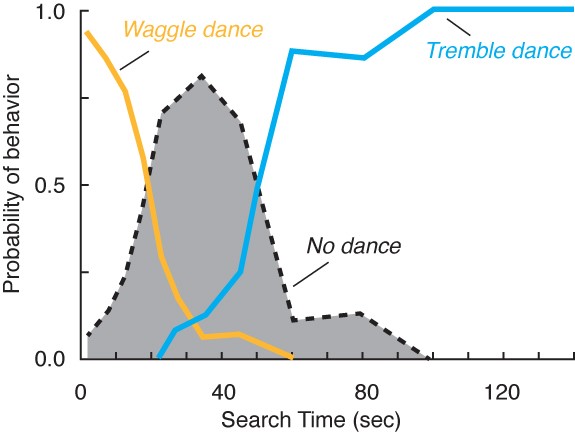

I was not surprised that the 15 nectar collectors were no longer performing waggle dances, for I was seeing that these bees were no longer getting “mobbed” by nectar receivers when they returned from their feeder. Instead, they were having difficulties finding bees willing to receive their loads of sugar syrup. But what really caught my attention, and gave me a mental jolt, was seeing that 3 of my 15 nectar collectors (20%) performed tremble dances that lasted several minutes when they came home. Cool! I wondered, were these three bees issuing strong calls for more bees in their colony to function as nectar receivers? It sure looked like it. This proved to be correct, as further studies showed. What I learned is shown in Fig. 4. If a nectar collector returns home from a rich nectar source and finds that she must search long and hard to find a nectar receiver, then she will perform tremble dances. So, at last, the decades-old mystery of what causes the tremble dance was solved!

Fig. 4. Dance behavior as a function of the in-hive search time for nectar collectors visiting a rich food source.

Postcript.

Several years later, in 2000, I learned that Karl von Frisch had always thought that the tremble dance must be an important signal—not a symptom of neurosis—and that he had said that he would award a prize to whoever deciphered the message of the tremble dance. Alas, Karl von Frisch died in the summer of 1982… five years before the summer of 1987, when my helpers and I performed the experiment that yielded the solution to this long-standing mystery.

I loved Tom’s latest book, such joy to read him!

Thank you, Paul. Your words are wonderfully encouraging. Good to know that you enjoyed reading my new book’s 20 short stories about the marvelous behaviors of worker honey bees.